|

|

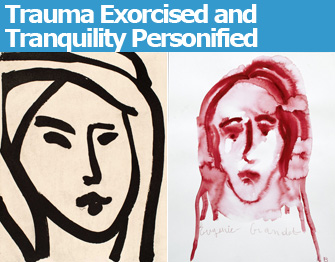

| Left: “Bédouine – Souvenir de Manon” (1947), an aquatint by Henri Matisse. © Sucession H. Matisse. Photo: Michael Matisse. Right: “Eugénie Grandet” (2009), a gouache drawing by Louise Bourgeois. Photo: Christopher Burke. © Adagp, Paris 2010. © Louise Bourgeois Trust. |

Louise Bourgeois, the French-born American artist who died this year at the age of 98, freely admitted that for her art was therapy – “a series of exorcisms” – and she spoke compellingly …

|

| Left: “Bédouine – Souvenir de Manon” (1947), an aquatint by Henri Matisse. © Sucession H. Matisse. Photo: Michael Matisse. Right: “Eugénie Grandet” (2009), a gouache drawing by Louise Bourgeois. Photo: Christopher Burke. © Adagp, Paris 2010. © Louise Bourgeois Trust. |

Louise Bourgeois, the French-born American artist who died this year at the age of 98, freely admitted that for her art was therapy – “a series of exorcisms” – and she spoke compellingly about it. A 1993 quotation, posted on the wall at the Maison de Balzac’s current exhibition “Louise Bourgeois: Moi, Eugénie Grandet,” sums it up beautifully: “Every morning, when I set to work, I exorcise a trauma – the word is not too strong. But that is not something you talk about; it’s something you do…. when I look at my work, I say to myself, ‘Louise, you have transformed a trauma into something very human, very joyful’.”

The works made for the show are integrated into the rooms of Balzac’s former home, furnished with some of his belongings and numerous portraits of him by various artists. In one of Bourgeois’s portraits of Eugénie Grandet, she looks relatively happy, with long hair and a Mona Lisa smile. This quickly changes to great sadness in the blood-red portrait pictured above. Another blood-red drawing shows a standing naked woman with a flailing, screaming upside-down baby in her stomach. The unending umbilical cord winds all around the woman’s body, and a phallic shape protrudes beneath her stomach.

Bourgeois’s trauma was very much her own, and she was unique in the way she could turn it into wholly original works of art that not only exorcised her own traumas but may just help others exorcise their own.

Matisse, who said that “details diminish the purity of lines and detract from their emotional intensity,” reduced most of his drawings to the very minimum, sometimes clumsily but most often elegantly. Some of the most wonderful prints in this show are from the powerful series made in 1931-32, which capture the movements of dancers and acrobats.

The exhibition, called “Une Autre Langue: Matisse et la Gravure,” covers Matisse’s entire career as a printmaker – he made some 900 graphic works using all the different printing techniques and illustrated over 80 books with his prints, including the famous Jazz, a copy of which is included here.

Maison de Balzac: 47 rue Raynouard, 75016 Paris. Tel.: 01 55 74 41 80. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 10am-6pm. Admission: €4. Through February 6. www.balzac.paris.fr

Mona Bismarck Foundation: 34 avenue de New-York, 75016 Paris. Tel.: 01 47 23 38 88. Open Tuesday-Saturday, noon-6:30pm. Free admission. Through February 15. www.monabismarck.org

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite