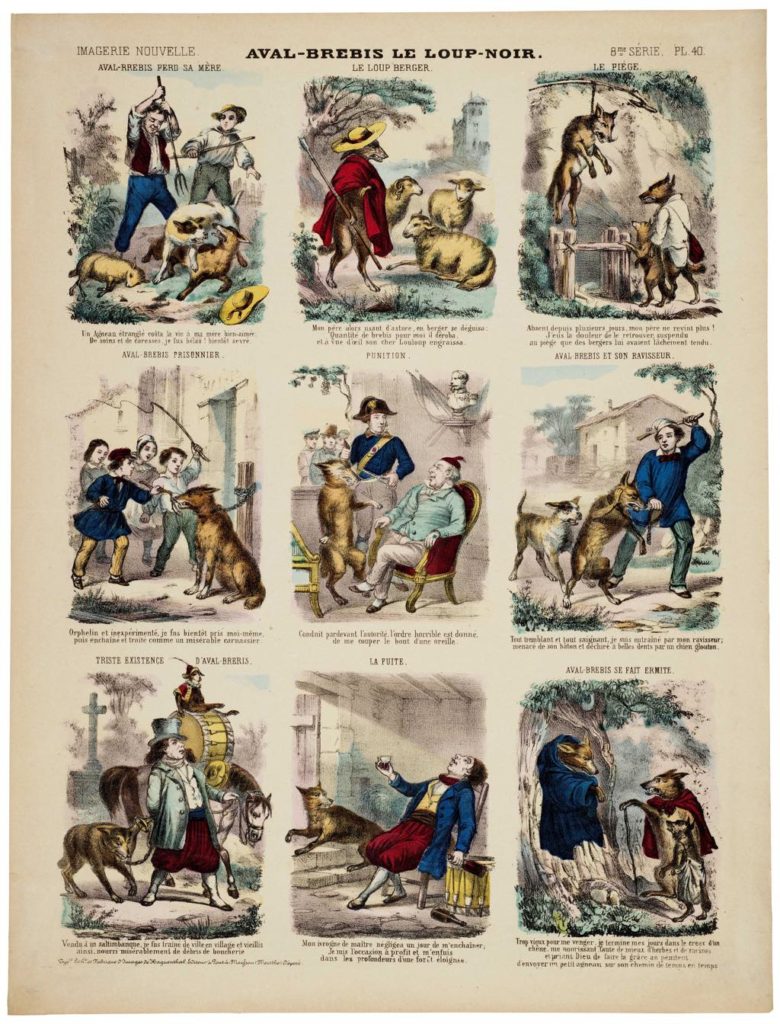

In French, the expression “image d’Épinal” refers to something that’s traditional, naively upbeat, clichéd, maybe even corny. The expression’s origin goes back to the Imagerie d’Épinal, founded in 1796, which became famous all over France for its brightly colored, simplified illustrations of fables and popular dictums. Some stories were laid out in panels, in an early form of the comic strip. These popular, inexpensive prints with often moralistic or propagandistic (promoting the greatness of Napoleon, for example, in the first half of the 19th century) messages were sold by traveling salesmen roaming the countryside and presumably brought a little color, humor and culture into the lives of people outside the big cities.

Today, the famous printing house in the town of Épinal in northeastern France lives on as the Maison Images d’Épinal, a private company that holds the archives and produces new prints, wallpaper, etc., while the next-door Musée d’Épinal, in a handsome modern building, is run by the city. The museum, which has a permanent exhibition on the history of the printing house, also holds temporary shows. The current one, “Loup! Qui Es-Tu,” looks at a topic – wolves – that is as hot today as it was in the 19th century, though for different reasons.

The wolf may be the ancestor of man’s best friend, the dog, but in the 19th century, it was man’s worst enemy, feared and despised. As the exhibition shows, the animal was accused of every imaginable perfidy: killing sheep (true), killing more sheep than it could eat (true), having a special liking for human flesh and especially that of babies (doubtful), and being the incarnation of the devil as the devourer of the symbol of Christ, the lamb (doubtful).

The complete eradication of wolves was seen as highly desirable, and – with the help of a cash bounty for each beast killed – was accomplished in France by 1937 (England and Wales, where the wolf had been wiped out by the 16th century, were far in advance).

In the 1990s, a different but related species of wolves, by then listed as an endangered species, began to infiltrate France from across the Italian border, and they are now protected following recognition of their important place in a healthy ecosystem.

Back in the 19th century, the Imagerie d’Épinal played an important role in anti-wolf propaganda with its posters of the big bad wolf and proto-comic strips recounting such tales as “Little Red Riding Hood” and La Fontaine’s Fables. In one of the latter, the wolf becomes a vegetarian so that humans will love him, but then realizes what hypocrites humans are when he sees some men eating lamb.

The exhibition traces the evolution of the human perception of wolves from terrifying killer (in the 19th-century images, it is always shown attacking or about to attack) to a friend of the ecosystem through images (from Épinal and elsewhere), films, objects and even a display of taxidermy wolves of different species.

Fear of the big bad wolf is by no means dead. In the late 1970s, the “Bête des Vosges,” an unidentified wolf-like beast that supposedly killed some 100 farm animals, spread hysteria in the Vosges Region, where Épinal happens to be located. The legend died down when the killings stopped (but not before a German resident suspected of owning the beast was practically lynched), only to return in the mid-1990s and again in 2011. Plus ça change …

Favorite