Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) is a slippery character. It’s hard to get a grip on who he was and what he did, partly because he did so many different things – he was a poet, artist, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, screenwriter, set designer and more – and partly because he didn’t always seem to care about the preservation of his work – he would draw on a blackboard and erase the results, for example, and often instructed assistants to destroy original manuscripts and drawings (they often disobeyed).

At the opening yesterday of the Maison Jean Cocteau in the town of Milly-la-Forêt, about an hour from Paris, French Culture Minister Frédéric Mitterrand described Cocteau as “insaisissable,” or elusive, which seems to me the mot juste.

Curator Dominique Païni decried the fact that Cocteau is so “poorly known,” which surprised me, since references to him seem ubiquitous in Paris – his sketches adorn the menus of restaurants he frequented, and the Palais Royal is never mentioned without his name (along with that of Colette, the other famous resident) coming up – but Païni noted that the Centre Pompidou doesn’t have a single work by Cocteau in its collection, although it devoted an exhibition to him in 2003, which he also curated (the Pompidou’s curators “practically held their noses,” he said). He also said that Cocteau would have received much more attention if he were alive today, calling him the “Jeff Koons of his day,” which not everyone would take as a compliment.

So, was Cocteau a talented dandy-dilettante or a multifaceted genius? His brilliance and creative energy cannot be denied, but he left no consistent œuvre to judge him on: he won acclaim for his films La Belle et la Bête and Orphée, which are still shown, but does anyone read his poetry or novels today? He had a wonderful facility for drawing and adorned nearly everything he wrote with sketches but created no major works of visual art. An early adopter of new technologies (as soon as felt-tip pens became available, he used them instead of pastels, and he took part in television shows right from the beginning of the medium), he liked to work fast and move on to something else.

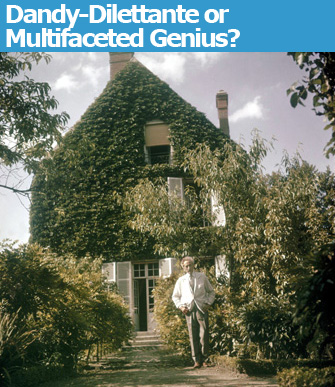

The house in Milly-la-Forêt that Cocteau bought in 1947 as a refuge from the Palais Royal is a fitting tribute to him, containing references to all these aspects of the man. Three rooms – the living room and his bedroom and study – were locked up by his companion (and adopted son), Edouard Dermit, when Cocteau died in 1963, and left untouched until Pierre Bergé (the business and life partner of the late Yves Saint Laurent), who was a friend of Cocteau, bought the house and its contents with the help of the local councils in 2002 and had it renovated.

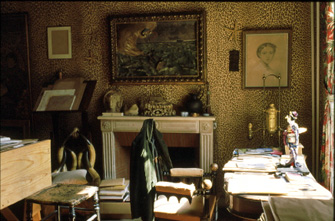

The furniture and objects in those three rooms have been minimally restored and cleaned (except the fabrics, which were in bad condition and had to be replicated). What do such rooms tell us? In this case, the small, rather fusty rooms are conventional in a way, with all the usual furnishings – a sofa, a narrow four-poster bed, etc. – yet hyper-kitsch (was Cocteau the inventor of kitsch?) and filled with bibelots and tchotchkes. The walls, ceiling, daybed and lampshades in the study are covered in leopard-skin-patterned paper and fabric, and a rather hideous painted plaster-relief image of a hot-air balloon surfing on a stormy ocean hangs over the mantelpiece. A dildo on the mantel is juxtaposed with an image of Christ. The living room boasts two enormous metal palm-tree lamps and a large painting by Christian Bérard, while a rather mundane mural depicting a château on a hill, perhaps painted by Cocteau’s lover, actor Jean Marais, covers one wall of the bedroom.

Other rooms have been converted into temporary and permanent exhibition spaces, and a library/gift shop. The permanent show presents portraits of Cocteau by some of the leading artists of the 20th century, who were also his friends: Picasso, Modigliani, Man Ray, Buffet and more. The current temporary exhibition, which will change annually, traces Cocteau’s life story through his works, including drawings, books, photos, excerpts from his films, interviews, etc. The photos document his affinity for very handsome young men, while the drawings offer some surprises: a wonderful portrait of Colette in charcoal and flour done on a wooden tabletop; a pencil and ink sketch of his neurasthenic friend Marcel Proust all bundled up in a hat and big overcoat with a fur collar and a mysterious object sticking out of his pocket; and sketches documenting Cocteau’s opium addiction and withdrawal from it.

Cocteau certainly had a genius for friendship. At the opening, Pierre Bergé, who was talking about how incredibly kind and polite Cocteau was, told a story about taking a two-hour walk with him one day. At the end of the walk, Cocteau said how wonderful it had been to wander like “two old Mandarins” exchanging confidences with him. “We hadn’t exchanged anything,” said Bergé. “He never stopped talking for a minute, but he was polite enough to say that we had had a dialogue.”

Cocteau, who died in the house, is buried in Milly-la-Forêt’s tiny 12th-century Chapelle Saint-Blaise des Simples, now open to the public, whose walls he decorated with frescoes. A recording of the gruff voice of Jean Marais describes its contents, and it is surrounded by a garden of “simples,” plants grown for their curative powers.

A highlight of a visit to the house is its enormous garden, crisscrossed by the moat of the charming small château next door, and the small wood behind it.

Chapelle Saint-Blaise des Simples: Tel.: 01 64 98 83 17. Open Wednesday-Sunday, 10am-noon and 2:30pm-6pm March 1-October 30; Wednesday-Sunday, 2pm-5pm November 1-January 15. Closed Monday and Tuesday and January 16-February 28. Admission: €2.50. www.chapelle-saint-blaise.org

Favorite