Matisse exhibitions don’t happen very often, and when one comes along, it is a major event. The eagerly awaited show at the Centre Pompidou, “Matisse: Like a Novel,” uses Louis Aragon’s Henri Matisse: Roman (1971) as a kind of framework to hang the exhibition on and an excuse to display a large number of books related to the artist, but the exhibition is basically a retrospective celebrating the 150th anniversary of his birth. The Centre Pompidou has trotted out some 100 works from its own substantial collection and supplemented it with pieces from other French museums.

A late starter as a painter, Matisse waited until he had finished his law studies before taking up the brush after falling in love with painting while convalescing from an illness (later in life, periods of convalescence would lead to many of his artistic breakthroughs, including the invention of the paper cutouts).

As a young man, he studied with Gustave Moreau, who presciently told his late-blooming pupil: “You are going to simplify painting.” Aragon, on the other hand, was convinced that Matisse would “make painting more complicated.”

Judge for yourself, but to my eye, it seems that by the end of his long life, Matisse did simplify painting. At the beginning of the show, we see him floundering as most young artists do: painting in classical style but also experimenting with Impressionism and Pointillism.

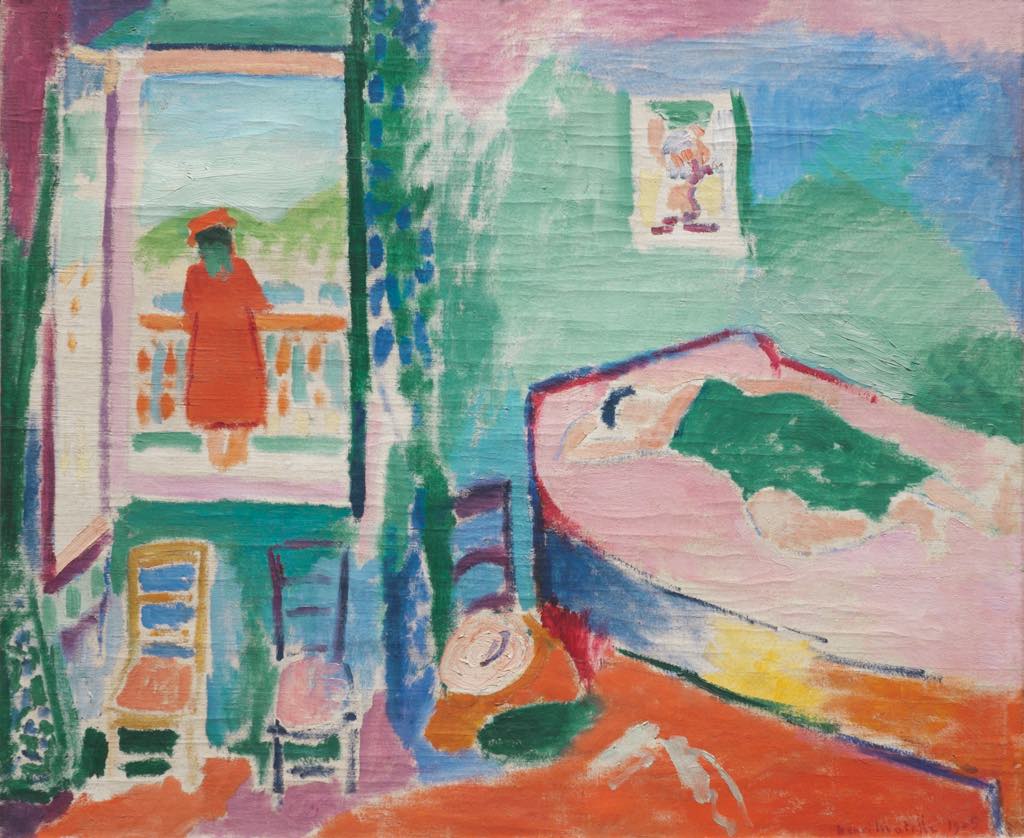

He didn’t come into his own until he associated with what were to become known as the Fauvist artists around 1905. That’s when his paintings exploded into loud, clashing colors, attracting the attention of the critics (the room his works were shown in at the Salon d’Automne was referred to as “la cage aux fauves” – the cage of wild beasts – by one of them), as well as such collectors as the Steins (Leo, Gertrude, Michael and Sarah) and the Cone sisters of Baltimore. Matisse defined a Fauvist painting as “a block of light formed by the harmony of several colors, in turn forming a space that is possible for the spirit (akin, I feel, to a musical chord).”

When Matisse moved on from his heady but short Fauvist period (it lasted only a couple of years), he concentrated on more decorative works like “Still Life with Aubergines” (1911), a large canvas in which the putative subject matter, three eggplants on a table, nearly drown amid the numerous textile and wallpaper patterns surrounding it. This picture contains many of the devices we identify with Matisse: patterned fabrics, clashing colors, horizontal surfaces rising up to face the viewer and a landscape seen through an open window, connecting the indoors with the outdoors.

In this vein, the show includes one of his wonderful goldfish paintings with an open window looking out on the Seine, “Interior with a Goldfish Bowl” (1914). It gives off a calmer feeling, with fewer patterns, beautiful shades of blue inside and out, touches of pink on the buildings outside and the red fish in their bowl by the window almost seeming to swim in the river.

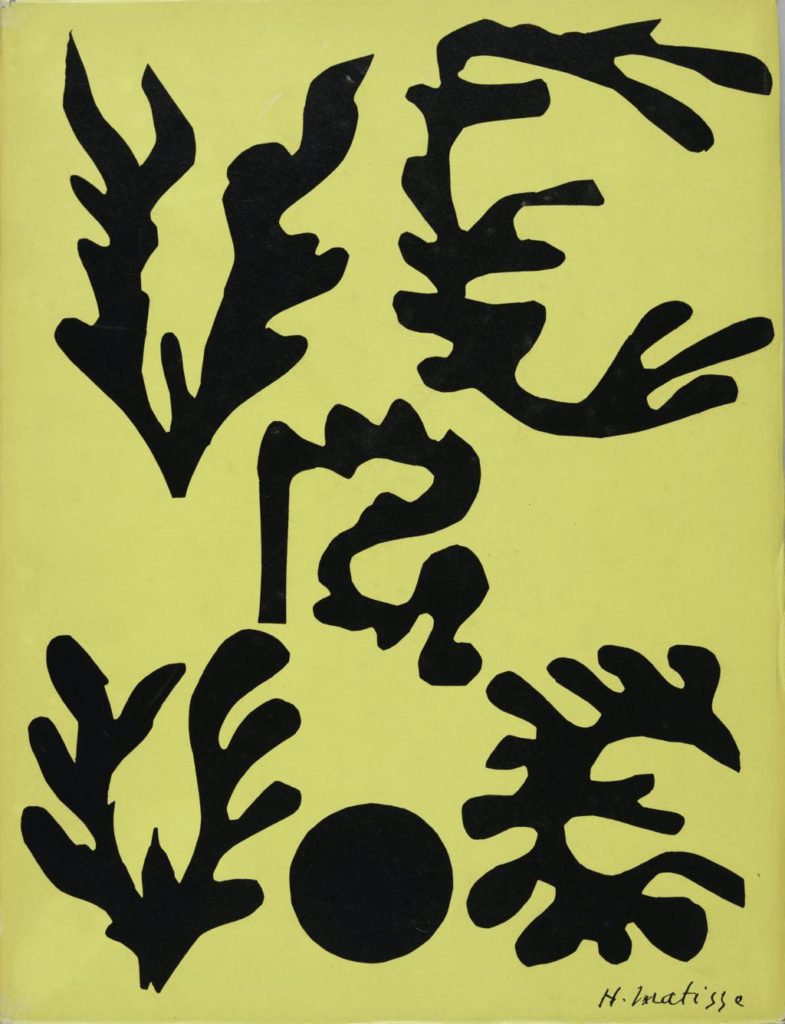

In keeping with the exhibition’s book theme, there are numerous volumes about Matisse or illustrated by him, from Poems by Stéphane Mallarmé to the art magazine Verve, for which he provided many cover designs, and, of course, the famed book Jazz, designed with the paper cutouts he resorted to when ill health made it impossible for him to paint.

At the end of his life, cutouts became not just a stopgap but his primary medium. Matisse’s genius for color bursts into full bloom in these wonderfully decorative pieces – compositions of cutouts as well as designs for theater sets and stained-glass windows and vestments for a chapel. Yes, they are simple – perhaps “distilled” is a better word – but intense and full of joy.

Favorite