Postimpressionist Cache In a Paris Suburb

The French Postimpressionist painter Maximilien Luce (1858-1941) bequeathed a hefty collection of his work – over 300 pieces – to the somewhat unfashionable town of Mantes-la-Jolie, west of Paris. Today the town is very proud of this inheritance and puts on regular shows at the Hôtel Dieu, next to the town’s magnificent 13th-century church, the Collégiale Notre-Dame. The current exhibition is “Maximilien Luce [Re]trouvailles.”

I came across the show by chance, after seeing a reference to it at the Musée des Impressionismes in Giverny, the splendid village where Monet made his home, which is just a few kilometers from Mantes along the valley of the River Seine.

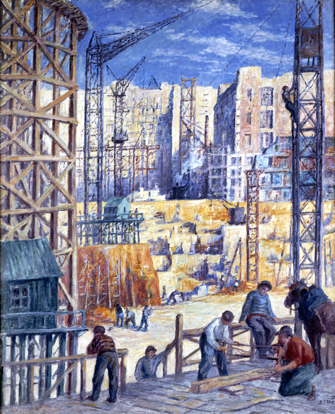

Throughout his long life, Luce remained committed to humanitarian and left-wing principles. His work includes numerous views celebrating the world of work: building sites, factory scenes and honest laborers doing their jobs.

Luce started his career as an engraver of drawings for newspapers, which gave him a perceptive eye for people and situations at a time when drawings were a popular way to describe and narrate events. In addition to selling them to the mainstream newspapers (he got paid 50 francs a go), he contributed many illustrations without charge to revolutionary and anarchist publications such as Temps Nouveaux, La Révolte and Le Père Peinard.

The skills he honed as a monochrome illustrator provided him with an important understanding of perspective, movement and the human form. As a young boy, he had witnessed the bloody events and aftermath of the 1871 Paris Commune insurrection. Its gruesome repression was a theme he illustrated later in “Vive la Commune!” (c. 1910) and the realistic, Goya-like “L’Exécution de Varlin” (1914-17).

In 1894, Luce was briefly thrown into prison, along with many other anarchist sympathizers, following the assassination of French President Sadi Carnot. When freed, he fled to Belgium, where he met the poet Émile Verhaeren, who became a close friend and introduced him into Brussels art circles. In 1889, he exhibited at the Salon des Vingt in the Belgian capital. One of Luce’s most striking paintings, “Fonderie à Charleroi” (1896) dates from this period.

This picture showing the fuming activity of the iron foundry reveals a mastery of color and perspective, with a dozen workers engaged in a range of activities in the foreground. The artist’s lifelong preoccupation with the world of work and the honesty of the working man began around this time.

Returning to France, Luce became well-

established enough to join the Paris club Artistes Indépendants, through which he became close friends with Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac and other artists and plunged into the world of pointillism and other experiments with color and effects.

The current exhibition at the Musée des Impressionismes in Giverny is devoted to the Spanish artist Joaquin Sorolla, who cited Luce as an influence in his treatment of nature, men at work and water. It is unclear whether the two men met, but it is intriguing to wonder what they might have talked about if they had; on the face of it there is little to connect the humble working-class Parisian painter and the posh society artist from Madrid, known for his dazzling light effects and overdressed Victorian ladies standing on windy beaches.

In his later years, Luce settled down with his lifelong companion Ambroisine Bouin in Rolleboise, a village on the Seine, where he produced many landscapes of sun-dappled woods, the mighty river with its steam tugs, and local people at work doing mundane tasks.

World War I saw Luce enter the field of war art, and some examples from this period are on show at Mantes. “Gare de l’Est sous la Neige” and “Poilus à la Gare de l’Est,” both painted in 1917, demonstrate his feeling for the fate of men during the war. As ever, news events influence the subject matter and approach taken by the artist.

In the 1930s, he returned to the work theme and produced some magnificent pieces, including “Chantier pour la Construction du Métro” (1931-34). It, and the earlier “Construction du Quai de Passy,” (1907) show

his interest in such then-unfashionable subjects as industry and engineering. Taken with Luce’s wartime pictures, they reminded me of the work of such British war artists as Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, John Lavery and Eric Ravilious.

Luce lived to witness the sad events in Paris during World War II and resigned from the independent artists’ club to protest discrimination against his Jewish colleagues during the German occupation of the city. Touchingly, he married his faithful companion, Ambroisine, shortly before he died at the age of 83.

Editor’s note: A few pictures mentioned in this review, including “Fonderie à Charleroi” and “Chantier pour la Construction du Métro,” have been lent to other museums since this article was written, and a show of Luce’s drawings and engravings, “Au Charbon ! Dessins et Gravures de Maximilien Luce,” has been added.

Favorite