|

|

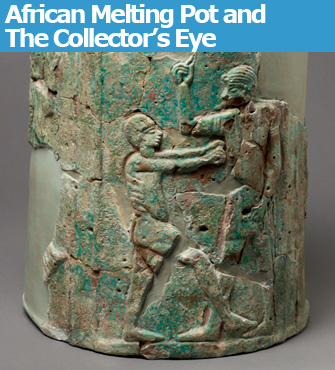

Cylinder decorated with festive ritual scenes, 1st century. © 2010 Musée du Louvre/Georges Poncet |

The Louvre often holds small temporary exhibitions that complement its own collections. While they don’t get as much attention in the press as the blockbuster shows, they are …

|

|

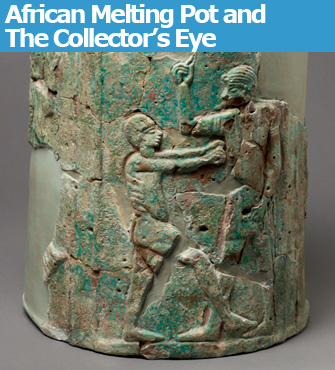

Cylinder decorated with festive ritual scenes, 1st century. © 2010 Musée du Louvre/Georges Poncet |

The Louvre often holds small temporary exhibitions that complement its own collections. While they don’t get as much attention in the press as the blockbuster shows, they are almost always well worth a visit. Here’s a look at two of them.

Meroe: An Empire on the Nile

King Tut never slept in Meroe, but this empire located in modern-day Sudan, which flourished between the third century B.C.E. and the fourth century C.E., was strongly influenced by the Egyptian Empire, as well as that of the Greco-Roman and other African civilizations.

The exhibition “Méroé, un Empire sur le Nil” (through September 6) starts off with a bang with a powerful sandstone sculpture of a trussed prisoner on his knees, impaled on a stake, his head forced back. No one could look at it without feeling his pain. Next to it is a larger sculpture, worn down by time and the elements, of a similarly trussed prisoner being devoured by a lion. These images of vanquished enemies, thought to have magical protective powers, vividly demonstrate the highly expressive artistic skills of this culture.

While the Meroitic civilization used Egyptian hieroglyphs for religious texts, it also had its own, purely phonetic cursive script, which was used for both sacred and profane texts. The exhibition includes a number of steles incised with images and writing in both alphabets. While the script, which transcribes an African language related to others still spoken today, was deciphered early in the 20th century, it is only starting to be understood now.

The Egyptian influence is obvious everywhere, but the polytheistic Meroitic people were by no means imitators. They were open to incorporating not only Egyptian gods into their world view, but also gods borrowed from other civilizations, notably the highly popular Dionysus, who had his own wine-drinking cult. The show includes an ithyphallic (the art historian’s polite way of saying “with an erection”) statue of the Egyptian god Amon, as well as several objects devoted to the cult of Dionysus. A locally made cylinder (pictured above) bears rough, cartoonish illustrations of ritual celebrations, with one mysterious scene showing two men dancing. The smaller one, who is naked, lifts one leg in the air and holds out his arms to a larger man as if asking for a hug.

Both high (royal and sacred) and low (e.g., roughly formed figurine/amulets) art from this melting pot of a civilization is presented in the exhibition, made with varying levels of craftsmanship. It is hard to say, for example, whether the goofy expression of King Amanakhabale on one of the steles is intentional or the result of a lack of skill on the part of the carver. Other works are more sophisticated, like a stele from the imperial city of Naga depicting Candace (Queen) Amanishakheto receiving the breath of life from the goddess Amesemi. Another fine piece from a temple in Naga is a carved relief profile of the face of a member of the royal family wearing a serene expression.

While the show offers some 200 artifacts – everything from pottery (one particularly handsome black earthenware pot is decorated with a frieze of stylized bulls using a Neolithic technique) to jewelry – it leaves you wanting to know more about this still-mysterious civilization. It will be interesting to see what pops up in the excavations being conducted by the Louvre’s Department of Egyptian Antiquities since 2007 near the city of Meroe.

The Motais de Narbonne Collection:

17th- and 18th-Century French and

Italian Paintings

|

|

|

“Vanité,” by Simon Renard de Saint-André. © 2009 Musée du Louvre/Pierre Ballif |

If you get to the Louvre before June 21, you can catch another small temporary exhibition that complements the Louvre’s own collection: “La Collection Motais de Narbonne: Tableaux Français et Italiens des XVIIe et XVIIIe Siècles.”

This collection of around 40 works, which includes paintings by such luminaries as Charles Le Brun, court painter at Versailles during the reign of Louis XIV, has been put together over the past 30 years by an art-loving Parisian couple, Héléna and Guy Motais de Narbonne. One of the reasons for showing it, according to the wall text, is to demonstrate that even today a decent collection of Old Masters can be put together by those with the means and the eye, but it must also be noted that the couple agreed to donate two of the works to the Louvre. Chosen by the museum’s curators, they are “The Return of the Prodigal Son” by Domenico Maria Viani (1668–1711), and “La Bataille entre les Amazones et les Grecs” by Claude Deruet (1588–1660). For visitors, one of the advantages of a show like this is the chance to see works that they would otherwise probably never get to lay eyes on.

While they are not all masterpieces, there are a number of striking works here, especially among the Italian paintings. Most are biblical or mythical scenes, with one fine still life, “Vanité,” by Simon Renard de Saint-André (1613-77), depicting – in addition to the traditional skull, candle and hourglass meant to remind us that our days are numbered – a book opened to an engraving of the resurrection of the dead.

Other notable works include a lovely “Annunciation” by Charles Poërson (1609-67) and the Caravagesque “David with the Head of Goliath” by Francesco Cairo (1607-65). In the latter, the light picks out the features on Goliath’s face and the muscled arm of the young David, who wears a feathered hat that casts a shadow over most of his face.

Musée du Louvre. Métro: Palais-Royal/Musée du Louvre. Tel.: 01 40 20 53 17. Open Wednesday-Monday, 9am-6pm (until 10pm on Wednesday and Friday). Closed Tuesday. Admission: €11. Meroe: through September 6. La Collection Motais de Narbonne: through June 21. www.louvre.fr

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Order the exhibition catalogue, Meroe: Un Empire Sur Le Nil: U.K., France

More reviews of Paris art shows.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite