The Palais de la Porte Dorée – a stunning Art Deco building opened in 1931 for the International Colonial Exhibition celebrating France’s worldwide empire – is now the home of the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration (and a tropical aquarium). Its permanent exhibition has just been completely revamped after three years of work and is twice the size it was before (the museum opened in 2007). It now does a fine job of celebrating the history and contributions of immigrants from former French colonies and other countries with exhibits that range from broad overviews of historical periods to spotlights on particular moments or on individuals or groups, liberally illustrated with photos, artworks, music, films and documents.

Like most Western countries, France welcomed immigrants when it needed them: in the 1960s, for example, when there was a shortfall of workers, they were recruited from France’s former North African colonies. While allowed to work and even granted nationality, they were shut out of Paris in what became high-rise ghettos in the suburbs, the scene of most of the recent rioting after a 17-year-old boy was shot dead by a policeman.

Nearly one in three French people is descended from immigrants, but as in most Western countries today, immigration is a fiery issue in France that wins votes for the far right, which supports suppressive policies and even advocates the expulsion of foreigners already in the country. In an attempt to pull far-right voters into their sphere, center-right politicians, including President Emmanuel Macron, are now taking a tougher stance on the issue. Critics have noted the paradox of the French state funding a museum on immigration at a time when the government is supporting tighter restrictions. One wonders what the fate of this museum will be if the far right ever succeeds in taking power.

Given all that, plus the continuing waves of migrants fleeing extreme poverty, war and political persecution in so many countries, creating a museum on the subject without offending anyone is a tricky proposition. The curators saw their primary role as educational, showing visitors how “the history of immigration is the history of the country.” In an attempt to assuage anti-immigrant fever, visitors are reminded that only 8 percent of the country’s population is foreign-born, not 23 percent, as many French people think.

Organized into 12 sections covering important milestones in the history of immigration, the show begins with the Code Noir, a law promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685 that not only defined the conditions of slavery in the French colonies but also called for the expulsion of all Jews from them.

France may pride itself on welcoming political refugees from other countries, but it has also sent many out into the world. After Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, for example, Protestants were required to convert to Catholicism or face persecution. By 1715, 180,000 Huguenots had fled France.

The French Revolution brought with it many changes in the status of foreigners. Slavery was banned in 1794, but it was reinstated by Napoleon in 1802 and not definitively outlawed until 1848, when the Republic was restored and political refugees from other European countries were welcomed in France and allowed to become citizens (an openness that lasted only about a year). Between 1642 and 1848, 1.4 million Africans had been captured and transported to the French colonies.

In 1790, foreigners who had lived for four years in France were allowed to become citizens by taking an oath. A year later, France’s disenfranchised Jews, numbering around 40,000, were granted citizenship and the right to vote.

The Revolution also led to another outflow from France, of some 150,000 royalists and aristocrats, known as the “émigrés,” who feared for their heads if they stayed.

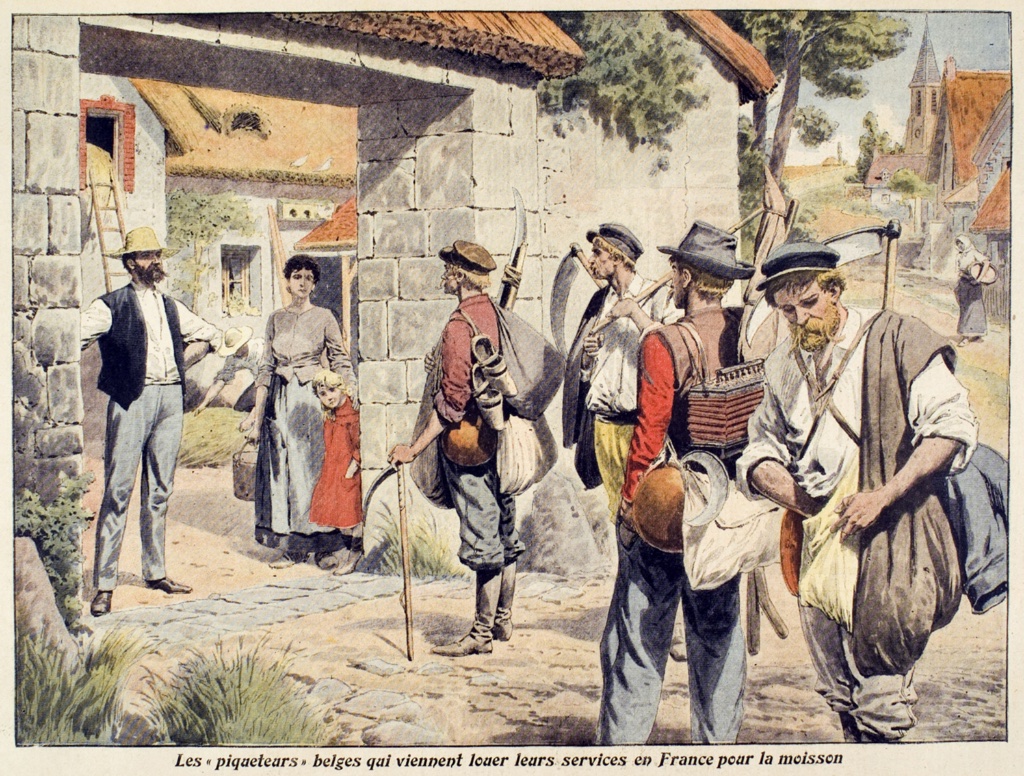

During periods of economic depression, anti-immigrant sentiment burgeoned in the country, as at the end of the 19th century, when Belgian and Italian immigrants were often attacked. Resentment of Jews, seen as threatening outsiders, also increased, culminating in the Dreyfus affair, when French Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of passing military secrets to the Germans, an affair that created a huge scandal and divided French society.

During World War I, France obliged citizens of its colonies to fight on its side. As of 1917, foreigners staying in France for over a week were required to apply for a special ID card. After the war, however, immigrants were welcomed to fill jobs and bolster the depleted population.

The museum brings to life the dry details of changes in laws regulating the presence of foreigners in France by telling the stories of some individuals. In 1915, during the genocide of Armenians in Turkey, for example, Melkon Bedrossian (1906-90), whose father had been killed in the Cilicia Massacres, was deported to the Syrian Desert, where he became separated from his mother and one of his sisters. He was then interned in a Lebanese orphanage, where Armenian children were “Turkified” and forcibly converted. After escaping to Greece in 1918, he made his way to France, where he obtained an employment contract in 1923. He eventually brought two of his sisters to France to join him in the Paris area. He fought and was wounded in World War II and was granted French citizenship after the war. His short biography is accompanied by a photo of him as a handsome, angry-looking young man and by a beautiful wooden box he had made, inlaid with an intricate pattern in mother-of-pearl.

Not surprisingly, the Colonial Exhibition of 1931, for which the Palais de la Porte Dorée was built, gets a good deal of coverage. To retain its status as a world power, France wanted to show off the “reservoir of manpower and raw materials” represented by its colonies.

One of the most entertaining parts of the museum is the Music Studio, a large, soundproofed room papered with album covers where visitors can relax and listen to playlists of the musical heritage bequeathed by immigrants to France, from Josephine Baker to Amàlia Rodrigues and today’s hip-hop artists. The playlists are also available here.

The irony of the monumental Palais de la Porte Dorée’s original role in championing French colonialism – its entire facade is covered with handsome bas-reliefs celebrating the people of the French colonies – has not been lost on commentators. Although the bas-reliefs remain, the tables have been turned inside, with immigrants, so many of them from former or present French colonies, being honored instead.

Favorite