It is strangely quiet now in the newly renovated Rodin Museum, located in the 18th-century Hôtel Biron. The handsome Versailles parquet, now shored up to support the weight of the master’s heavy statues, makes nary a squeak (it used to make so much noise that the museum guides had to shout to be heard over it). The cracks in the walls have been plastered over and covered with a chic shade of grayish-green paint specially created for the museum by Farrow & Ball, posh purveyors of the colors du jour. The works are lit by the latest in track lighting, and the new graphics offer a good sense of what you are seeing in each room. The dust-free crystal chandeliers sparkle, and the carved-wood paneling in the gracious oval corner rooms gleams. The age of this elegant mansion is visible only in the spotty, cloudy mirrors.

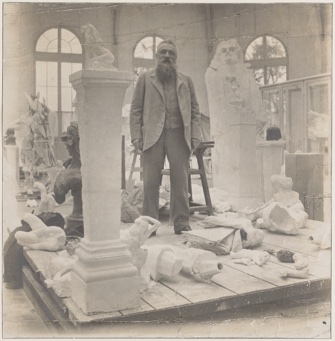

During the three-year renovation, the museum also took the opportunity to pull many plaster casts out of the reserves and restore them, the better to illustrate the evolution of some of the master’s most important works through many states – it is staggering to see how much work went into each sculpture.

Rodin (1840-1917) lived and worked in the Hôtel Biron as of 1908, and one of those oval corner rooms helps to satisfy visitors’ curiosity about his life there with period furnishings and photos and objects that belonged to him: fragments of antique statues, paintings and other works, including a curious 19th-century bronze statue of the god of longevity from Japan. These pieces are interspersed with his own works, all displayed on crates or simple sculptors’ stands as shown in contemporary photos of his rooms. Rodin’s then-radical view was that stands should be as simple as possible, and the new wooden stands displaying his work throughout the museum are accordingly discreet. Modern in design, their wood matches the parquet.

The visit starts out chronologically with some of the young artist’s early sculptures and paintings, including a group of lovely landscapes that have a Turneresque quality in their use of light. From there on, visitors find a succession of favorites – among mine are his many studies for a statue of Balzac; the monumental “The Gates of Hell” and “The Burghers of Calais”; “The Walking Man” (pictured at the top of this page); and the theatrically emotional “The Prodigal Son.”

One room contains the work of Rodin’s talented and tragic pupil and lover Camille Claudel (exhibiting her work was a stipulation of his gift of his own work to the state), and another a few masterworks from his collection of paintings, including pictures by Monet and Van Gogh. The show continues outside in the extensive gardens, where “The Thinker” ponders, the unfinished “Gates of Hell” remain closed and “The Burghers of Calais” await their sad fate.

Has all this cleanliness and solidity stolen the soul of this wonderful museum, where one used to have the impression that the master had just stepped out for a break from the heavy work of making statues and might be back again any minute? Not really. Great care has been taken to be faithful to the artist, his work and the building, and while you may miss the creaky charm of its former dilapidated state, which seemed more appropriate for a bohemian artist than this elegant interior, you will leave more than ever convinced that Rodin was truly a genius and glad that his home will last for at least another century.

Favorite