Like many exhibitions I have seen in France, the ambitious “Out of the Shadows: Sculptures from Southwest Congo,” at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, is full of fascinating and wonderful objects but covers too much ground and offers so much information that an ordinary visitor feels exhausted, overwhelmed and confused by the end.

The show focuses on Bandundu, a former province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo that now includes the provinces of Kwango, Kwilu, Mai-Ndombe and Kinshasa, with a population of 28 million made up dozens of different cultures that have produced an “extraordinary variety” of statues, masks and other everyday objects. Therein lies the problem. That extraordinary variety makes it extremely difficult to present a coherent, easy-to-follow narrative for visitors.

This highly didactic exhibition would have greatly benefited from focusing on works from one culture (the related Yaka and Suku cultures, for example, which play a large role in the show) rather than trying to cover so many different ones with so many different objects and functions. I spent a good three hours there and read almost all of the texts. Some interesting details stuck in my mind – the strange turned-up, elephant-trunk-like noses on many Yaka and Suku sculptures, for example, which probably represented “body odor and carnal desire” – but the multitude of exhibits and explanations of functions made it difficult to keep it all straight in my mind.

Another complaint I have is with the insensitive title of the show; its English translation “Out of the Shadows” (“La Part de l’Ombre,” in French, or literally, “from the shadows”) calls to mind such dated and racist epithets as “darkest Africa” or the “dark continent.” It also has a condescending tone, as if only such exhibitions in Western museums could shed light on the subject.

That said, the show, which presents some 160 objects, most of them dating from between 1875 and 1950, is well worth seeing for the objects themselves. As a little appetizer, four statues displayed at the beginning illustrate their incredible variety, ranging from a wooden sculpture of a squatting man with his head resting on his hand à la Rodin’s “The Thinker,” from the Mbala culture, to a rough mpwwu statue from the Yanzi culture. Attached to the village chief, the latter was probably endowed with healing powers. It and many of the other works in the show remind us of how African sculpture influenced so many modern Western artists when they discovered it– think of Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” for example.

The show then displays a series of marvelous masks used during male initiation and other rites by different cultures, followed by a wealth of sculptures. Then there is a presentation of some of the scholars and others who studied the area’s cultures, interspersed with a few historical stories and two contemporary paintings commissioned by the museum from Jean-Claude Lofenia Mpoo and Enyejo Bakaka Flory. As if that weren’t enough, the final section covers carved weapons, tools, ivory pendants, headrests, stools, and divinatory instruments. It is nothing if not thorough in covering the sculpture of the region.

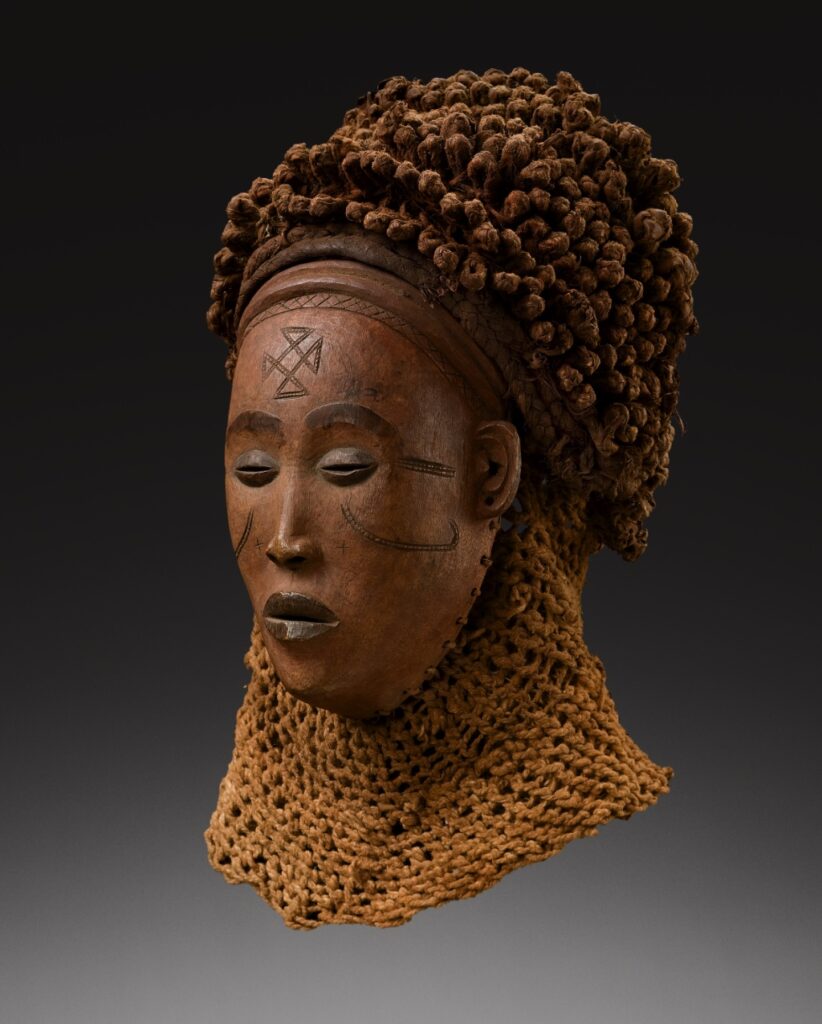

Your mind will be blown by many of these works, whether wonderfully refined, like the beautiful female pwo mask (pictured above) from the Chokwe (Tshokwe in French) culture (which traces descent through the matrilineal line), or extremely rough, like the ugly katoyo mask from the same people displayed next to it, representing an ancestral spirit dressed up as a white man, which was used to play a bawdy buffoon during dance performances.

One takeaway from the show is the fact that almost all of these objects had a function (as part of initiation, enthronement, healing or funerary rituals, or as charms), whether we now know what it is or not, but that we Westerners, save those who have closely studied the subject, can only really appreciate them for their artistic value. In fact, until Western collectors came along and gave them monetary value, many of these objects, notably the initiation masks, would have been routinely destroyed once they had served their purpose.

One more thing: while the name of the person who collected each object, when known, is noted on the labels, I saw no mention of whether these pieces, most of which are from the Belgian Royal Museum for Central Africa-Tervuren, along with some from private collections, were legitimately obtained. Now that the issue of restitution of looted objects from Africa and other places is finally a hot topic in the international museum world, it would have been interesting to see a word on the subject.

Favorite