To the uneducated eye, traditional Chinese landscape paintings may all look pretty much the same, with their tall, pointy mountains, misty skies and tiny figures, but each one is not only an individual work of art but also a compendium of the history of the genre, carefully encoded and recorded on the work, and often offers clues to the artist’s biography and political events in his lifetime. The exhibition “Painting Apart from the World: Monks and Scholars of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” (“Peindre Hors du Monde, Moines et Lettrés des Dynasties Ming et Qing”) at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, opens our eyes to a fascinating world that is a fascinating world that is superficially familiar but essentially unknown to many of us.

The one hundred paintings in the show are from the Chih Lo Lou (“Pavilion of Perfect Bliss”) Collection brought together by Ho Iu-kwong (1907–2006) and recently donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Art by his family. The collection covers a troubled period in Chinese history: the transition from the Ming (1368–1644) to the Qing (1644–1912) Dynasty.

During the prosperous years of the Ming Dynasty in South China, the wealth of the Suzhou region allowed many scholars to retreat to nature and follow their interest in literature, calligraphy and painting, although some of the painters featured here actually left society behind after being accused of corruption or cheating on their exams, as was the case of the “enfant terrible” and brilliant painter Tang Yin, who depicts himself meditating on the shore of a lake.

The local Wu School is represented here by its founder, Shen Zhou (1427-1509) and his most prominent follower, Wen Zhengming (1470–1559), with his bold compositions and almost pointillist style. Their paintings often depict the tiny figure of a scholar studying in a pavilion nearly hidden amid the immensity of nature. The image above zooms in on a detail showing a well-read 11-year-old boy hard at work with his books in Shen Zhou’s “Little Qian in the Study” (detail, 1483).

The calligraphic inscriptions on these works reach back into the history of Chinese painting and indicate not only the name of the painter of the work itself but also the name of the painter from the past whose style is being emulated. Other information includes dates, the names of subsequent owners of the work and sometimes poetry referring to the image. The late Ming Dynasty artists Dong Qichang (1555–1636) and Lan Ying (1585-c. 1664) took the “art of reference” to new heights, painting “in the style of” and paying explicit homage to past masters. The show includes the latter’s series of 12 vertical landscape scrolls, each in the style of a different painter from the past, creating a sort of guide to the history of Chinese painting.

While we may think of all traditional Chinese paintings as being vertical scrolls, the show makes it clear that many formats were used, including horizontal scrolls, rectangular and fan-shaped sheets, and albums. The painting and calligraphy styles here are also extremely diverse, not at all as rigid as one might think given the heavy presence of and reverence for the past.

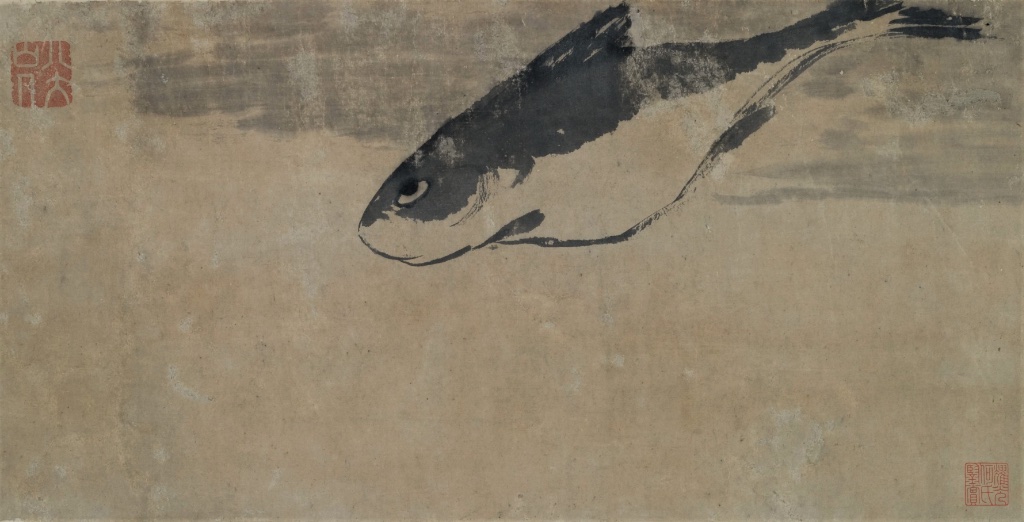

This becomes clear most interestingly during the transition between the two dynasties, when enemies of the changeover to the Manchu-ruled Qing Dynasty retreated to the mountains more to save their own skins than for cultural reasons. Some painters committed suicide or refused to serve the new rulers, while other Ming loyalists like Bada Shanren (born Zhu Da, 1626-1705) and Shitao (born Zhu Ruoji, 1642-1707) became monks to save their lives. In their forced retreat from the world, they brought a new simplicity and naturalness to their paintings. Examples are Bada Shanren’s “Fish” and Shitao’s “Landscapes Illustrating Poems by Huang Yanlü.”

Those unreal–looking pointy mountains in Chinese paintings, by the way, are not as fantastic as they seem. They really exist, as shown in the exhibition by a slideshow of black and white photos of the Huang Mountains taken by French photographer Marc Riboud (1923-2016).

This exhibition presents a manageable slice of the thousands of years of Chinese art history, with an amazing variety of styles and subjects that brings out the great individuality within what might at first glance seem to be great conformity. After seeing it, you might just want to retreat to the mountains.

Favorite