|

|

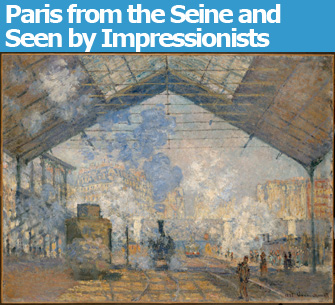

“La Gare Saint-Lazare” by Claude Monet. © RMN (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski |

It’s a shame that the exhibition “Paris aux Temps des Impressionnistes” is closing at the end of July, since this stimulating show at the Hôtel de Ville is …

|

|

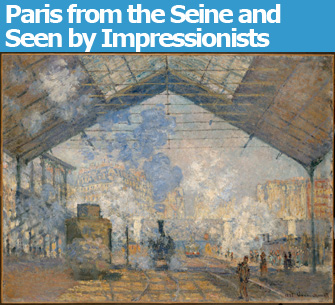

“La Gare Saint-Lazare” by Claude Monet. © RMN (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski |

It’s a shame that the exhibition “Paris aux Temps des Impressionnistes” is closing at the end of July, since this stimulating show at the Hôtel de Ville is the perfect companion piece to the new exhibition running concurrently there, “Paris sur Seine.”

“Paris aux Temps des Impressionnistes,” which includes 60 paintings and 60 drawings from the Musee d’Orsay (currently partially closed for renovation), starts off nicely by setting the stage for the arrival of a new modernity in art by showing us the improved Paris that was being developed in the city in the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th as Baron Haussmann cleared out slums (they would have been prime real estate today), plowed wide boulevards through the city and lined them with stately apartment buildings.

The Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent uprising of the Commune in 1871 further helped clear out the old – the Tuileries Palace and Hôtel de Ville were burnt down (the latter was rebuilt exactly as it had been) – while new entertainments for both the upper and working classes proliferated, with new cabarets, concert-cafés, guinguettes (dance halls), theaters (among them the Opera Garnier) and parks providing plenty of color for the Impressionist paintbrush. In the meantime, the trendy new international expositions were introducing the masses to the wonders of modern technology: electricity, moving sidewalks and so on.

Enter the Impressionists, who – even though they are now perhaps better known for their rural scenes – were eager to find new ways to express the excitement of this forward-looking world. Here we have one of Monet’s views of the Gare Saint-Lazare, in which he captured the heaving power of the great, smoke-bellowing locomotives, with some Haussmannian buildings providing the backdrop.

The exhibition, which concentrates on scenes from daily life, complemented by a slide show of photos from the era, also has a section devoted to “tragic Paris,” with images of the depredations of war and the violent suppression of the Commune – notably in “La Commune,” a large painting by Maximilien Luce in which the bodies of victims lie in the gray shadows in the foreground while the sun shines on the brightly colored shuttered storefronts in the background.

While most of the usual suspects are here – a couple of mushy Renoirs, a couple of unfamiliar Van Goghs, several wonderful paintings and drawings by Degas and many more – there are also a number of admirable works by less-familiar names, among them Canadian James Wilson Morrice, Frank Myers Boggs, Steinlein, Jean Béraud, Giuseppe De Nittis, Giovanni Boldini, Jacques-Emile Blanche (who painted the famous portrait of Proust) and more.

If you can, try to see the Impressionist show before it ends on July 30, and go as early in the day as possible to avoid long waits.

“Paris sur Seine,” which sets out to define and illustrate the changing role of the river over the centuries, begins much further back in time, with beautiful 15th-century maps of Paris, and tells its story entertainingly with prints, photos and films.

The Seine has been all things to Paris: protector (the first inhabitants set up housekeeping on the Ile de la Cité, from which they could see their enemies arriving), source of water, sewer,

|

|

“La Joute des Mariniers, entre le Pont Notre-Dame et le Pont au Change” (1715-1793) by Nicolas Jean-Baptiste Raguenet.. © Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet |

highway, shipping channel, commercial center, entertainment center and even a place to live for some. The river was packed not only with boats, but also with floating bathhouses and laundry barges. The banks were crowded with water carriers scoopings water out of the river for their customers, while dyers and tripe-makers made colorful additions to the water and shops lined both shores and bridges.

Until Paris’s importance as a port ebbed with the construction of a system of canals connecting the city with the north in the early 19th century and later with the inauguration of train and road networks, the city was primarily provisioned by boats, which had to wait sometimes for up to a month in the jammed river to discharge their goods and pay duties to the eagle-eyed customs men standing in their boats.

The fun began when most of these labors were banished from the river. Fireworks, jousting tournaments on boats, and swimming and fishing competitions were among the festivities.

Swimming in the Seine was always forbidden but there were always scofflaws, some of whom shocked neighbors with their scandalous behavior. And there were floating pools like the Piscine Deligny, which was in use for nearly two centuries before it sank one night in 1993.

It isn’t all fun and games along the Seine today, however. The national government despoiled the banks of the river by running a highway along it in 1967, and since then the city of Paris has been trying to take back the Seine with such laudable efforts as the closure of the road on each bank every Sunday in favor of walkers and cyclists, and the creation of Paris Plages, an annual summer event that brings a pool, restaurants, activities and, yes, a sandy beach, to the shores of the Seine. The most recent effort is a plan to permanently close some stretches of the Seine-side road, “civilize” others with stoplight and greenery, and place a floating movie screen on the water.

A note on the famous bateaux mouches, those floating behemoths ferrying tourists up and down the river with their squawking multilingual soundtracks and glaring floodlights. The original bateaux mouches, which began running in 1867, were water buses. The opening of the Métro in the early 20th century was the killer app that eventually guaranteed their disappearance. They officially went out of business in 1934, but were revived after World War II for the tourist trade and are now a beloved and familiar part of the image of Paris.

Hôtel de Ville de Paris: 29, rue de Rivoli, 75004 Paris. Métro: Hôtel de Ville. Tel. 01 42 76 51 53. Open Monday-Saturday, 10am-7pm. Closed Sunday and public holidays. Admission: free. “Paris aux Temps des Impressionnistes”: through July 30. “Paris sur Seine”: through September 17. www.paris.fr

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2011 Paris Update