Paul Klee (1879-1940) is generally acknowledged as one of the greats of modern art, but it’s difficult to think of a single powerful work or style that represents him, the way “Guernica” might, for example, pop into your mind when you think of Picasso. If you Google Paul Klee and click on “images” and “most famous paintings,” you will see a screenful of whimsical, colorful works, but nothing that leaps out at you. So what makes him a great artist?

The current retrospective “Paul Klee: L’Ironie à l’Œuvre” at the Centre Pompidou, with no fewer than 230 works, convinced me that, even if he was not a knockout artist, he was a far more interesting one than I had realized.

Like Monet, Klee started out as a caricaturist, and a very talented one. His ironic (and often self-deprecating) sense of humor is evident in many of the drawings shown here, such as “The Sensitive Artist,” a sketch of a mournful man, pencil in hand, leaning his head on his hand, or “The Artist Creating,” in which the subject has a mad look in his eye as he sketches away, both made in 1919.

A trip to Italy in 1901-02 was crucial to the artist’s development as he realized that he had to find a way to avoid being a mere imitator of all the great artists who had gone before him. He found the solution in satire and irony. “I serve beauty with its opposite,” he said.

Like Kandinsky, who taught at the Bauhaus at the same time, Klee took an intellectual, philosophical approach to art. The child of musicians, he was a musician himself and sometimes correlated musical notation with elements of his paintings to create a composition.

As a young artist he was convinced that he had no color sense and could not paint, but that changed after he was exposed to the work of

While he was influenced by and dabbled in many different movements, he never fully conformed to any of them. He invented his own forms of Pointillism and Divisionism, and felt that Cubism robbed figures of their vitality by enclosing them. And he never really embraced pure abstraction. Even the geometric abstraction of “Eros” (1923), with its bands of colors and two arrows pointing at each other, is representative – of the sex act, in this case.

Basically, he didn’t like to follow rules. One of his admirers, the composer Pierre Boulez, noted that the great thing about him was that he made rules and then broke them.

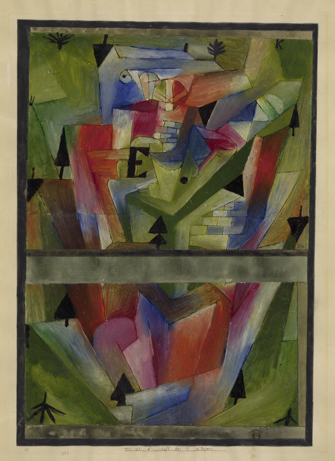

Klee’s love for the theater and the circus can be seen in the playful, childlike look of many of his works but, toward the end of his life,

work took on a darker tone as he became ill and was dismissed from his teaching job by the Nazis, who mocked and condemned his work as degenerate. The ironically titled piece pictured at the top of this page, “High Spirits” (1939), shows a precariously balanced tightrope walker, perhaps a metaphor for the position of the artist himelf.

The last work in the show, “Angelus Militans,” painted in a frenzy of productivity in 1940, the year he died, depicts an angel outlined in black like stained glass, its golden wings spread wide, seemingly ready to fly away from this earth.

Even after seeing the exhibition, I can’t say that there is one painting that stood out for me. What I was left with instead was an impression of a curious, intelligent, imaginative, hard-working artist with a sense of humour and an unending desire to learn and improve. For Klee, making art seems to have been an intellectual exercise that involved lots of play – with ideas, with lines and with colors – a good approach to any endeavor. Don’t miss this fascinating exhibition.

Favorite