Picasso liked to read the funny papers, and one of his suppliers was none other than Gertrude Stein, who would save the “Katzenjammer Kids” and other comics for him from American newspapers.

That’s just one of the many interesting facts learned at the Musée Picasso’s new exhibition, “Picasso et la Bande Dessinée,” which is accompanied by a second show about another art form Picasso indulged in, “Picasso Poète.”

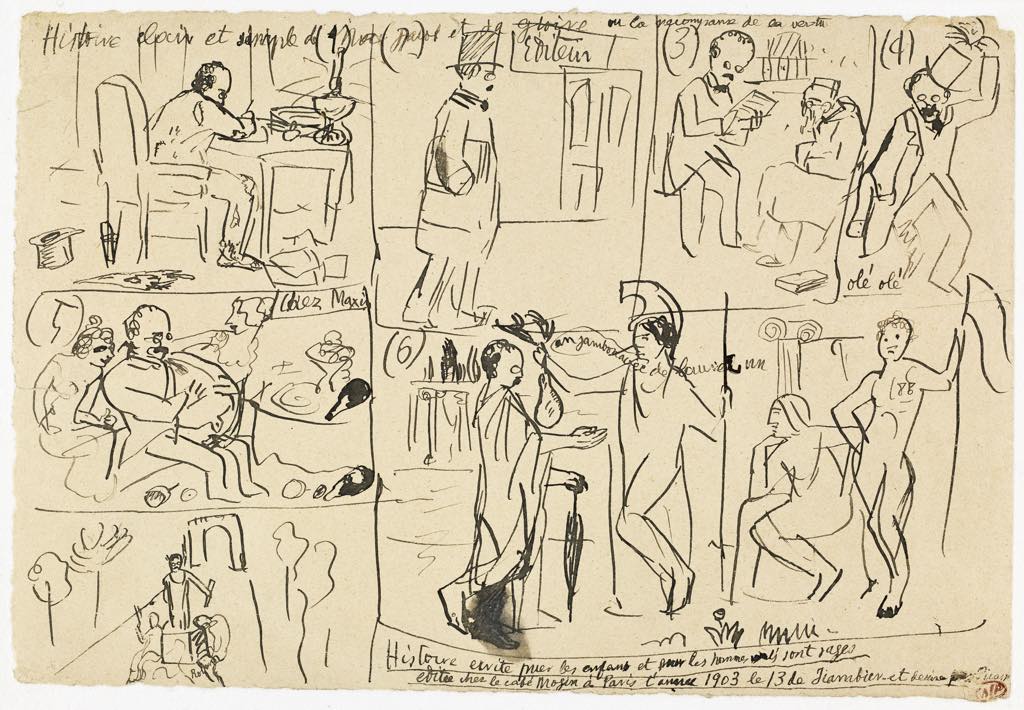

“Picasso and the Comic Strip” looks at its subject from every possible angle, showing how surprisingly rich the topic is. We see how Picasso experimented with the comic strip form himself at various times in his life, starting when he was 13 years old, using sequences of panels and even speech bubbles, and how he appropriated the visual codes of comics in many of his paintings. Even the Goyaesque “Dream and Lie of Franco” (1937), not exactly a humorous topic, tells its tragic story through panels.

There are also many comic strips in which Picasso himself and his famous paintings featured over the years, by everyone from Art Spiegelman to Tintin author Hergé. There is even a comic book biography, La Vie Imagée de Pablo Picasso (1951), written by chief Surrealist André Breton and Benjamin Péret.

A number of contemporary comic artists, among them Clément Oubrerie and Marina Savani, have been commissioned to create their own strips, inspired by Picasso or featuring him as a character, for the exhibition.

Comic-strip style influenced many of the artist’s paintings as well. British art critic Jonathan Jones has contended that even Picasso’s famous portrait of Gertrude Stein, with its realistically painted body and mismatching, mask-like face with flat planes, was inspired by the graphic world of comics.

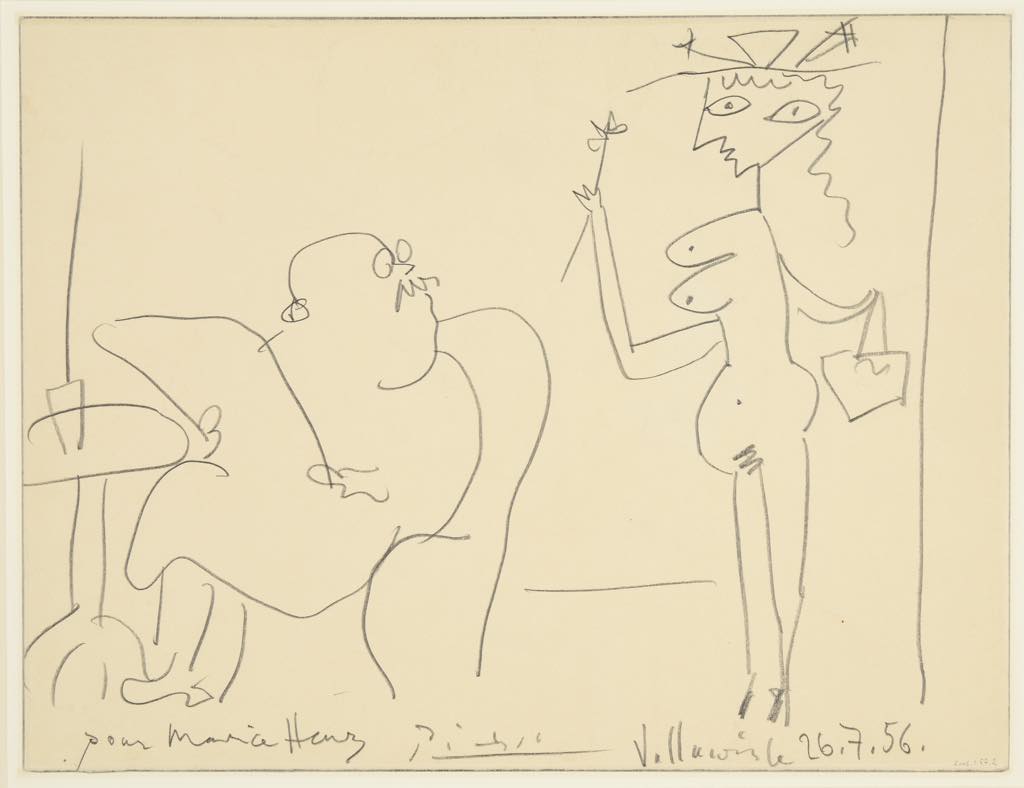

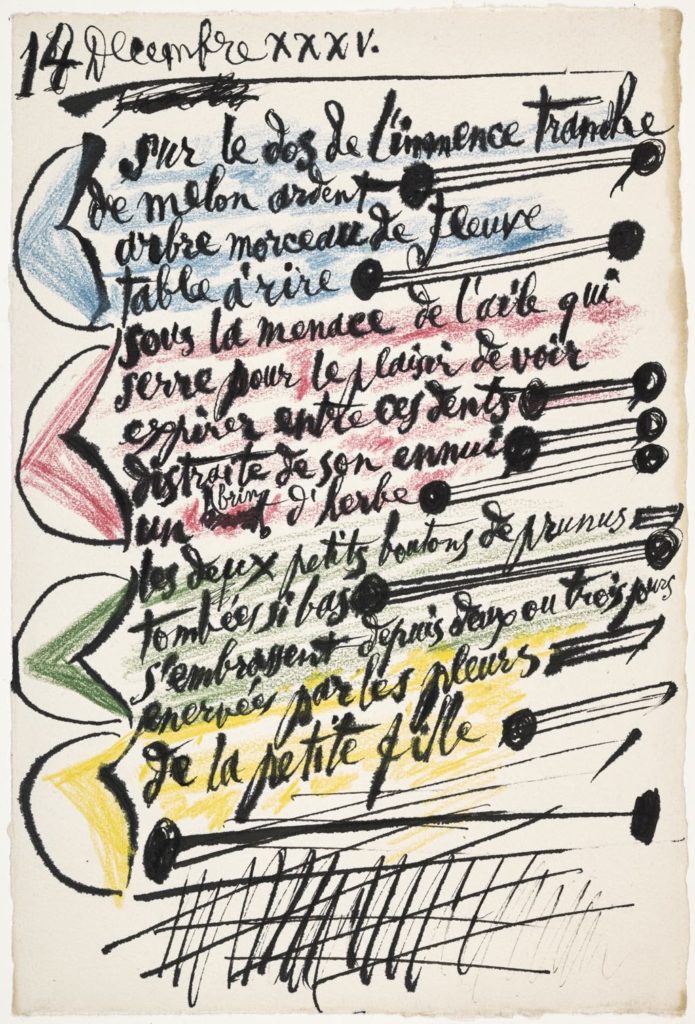

The second exhibition, “Picasso the Poet,” is equally fascinating and well-documented. While I knew that Picasso had illustrated books of poetry, I was unaware that he also wrote poetry and illustrated some of his own compositions to create works that spoke with both words and images.

Like his enjoyment of cartoons, Picasso’s love for literature had its roots in his youth, when he read such authors as Alfred de Vigny and Joan Maragall. Later, words and letters were used playfully in his Cubist paintings: the letters “JOU,” for example, could refer to the newspaper (journal in French) depicted in a painting, jour (day) or jouer (to play). He sometimes formed images from carefully arranged sentences or decorated his poems with color.

In the early days in Paris, Picasso moved in poetic circles and was a close friend of many of the greats or the day, including Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob and Paul Éluard.

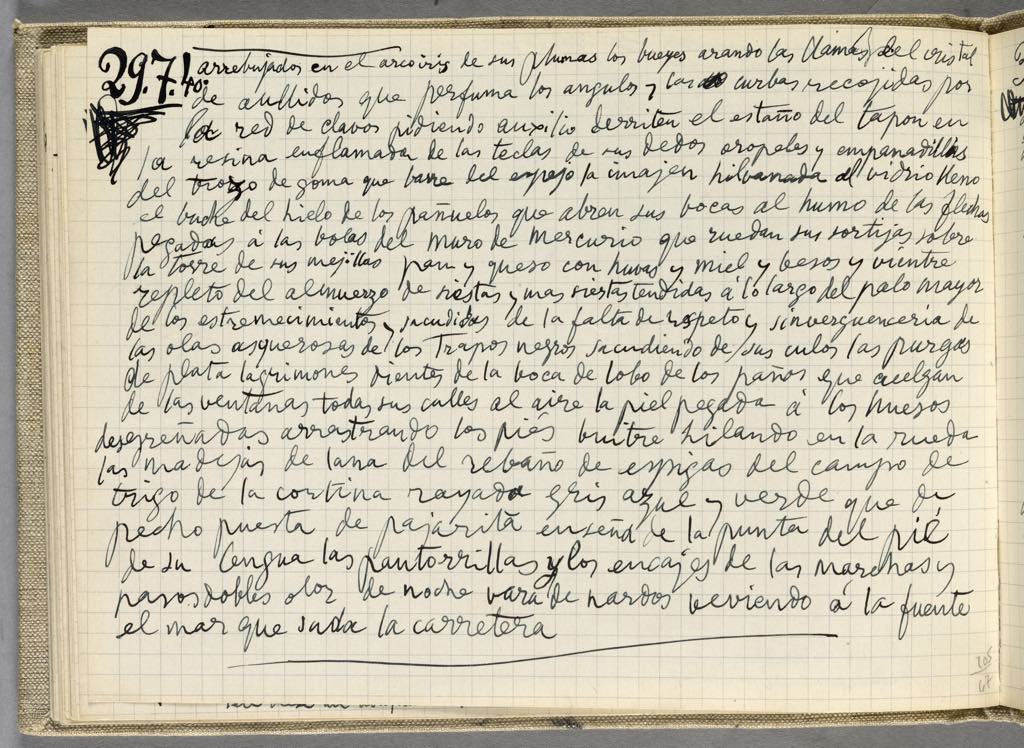

His own poetic muse really took over while he was staying in Boisgeloup, a village not far from Paris, in 1935, after his wife Olga left him upon learning of his long-term affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter. A torrent of words instead of images began to flow from his pen, resulting in stream-of-consciousness lines like these:

if I should go outside the wolves would come to eat out of my hand

just as my room would seem to be outside of me my other earnings

would go off around the world smashed into smithereens.

Between 1935 and ’59 alone, Picasso wrote some 340 poems. The manuscripts presented in the show demonstrate, as the curators put it, “the close links between his writing and painting” and to what point “the complexity of the work on the text (collage, repetitions, variations) echoes the pictorial process.”

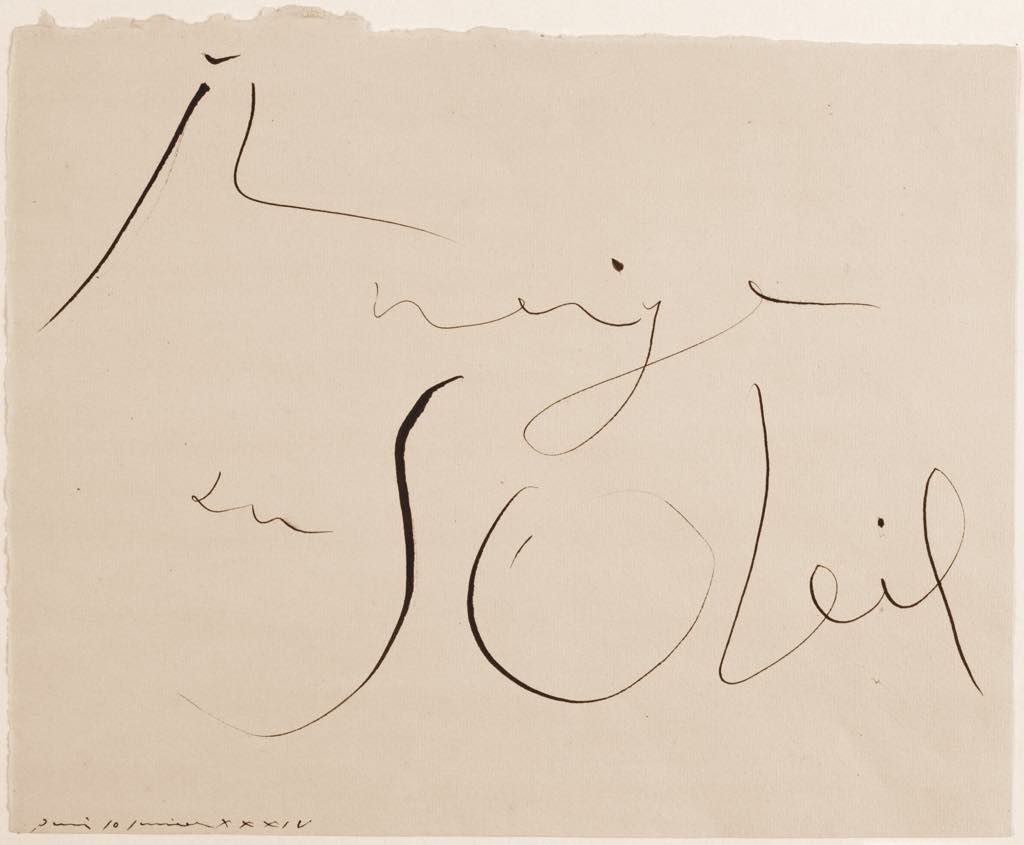

As Picasso once said, “One can write a painting in words just as one can paint sensations in a poem.” While staying in Juan-les-Pins for a couple of months later in 1935, he spent his time writing and drawing on fold sheets of Arches paper. Many of these works were experiments in drawing Walter, and some later developed into full-fledged paintings.

Between then and 1959, poetry became an integral part of his artistic practice. He scribbled his unpunctuated, oft-corrected lines in notebooks and on drawing paper, scratch paper, envelopes and even toilet paper. As he often did with his paintings, he sometimes made many versions of the same subject, one example being the poem “lengua de fuego” (tongue of fire), for which he created 18 versions.

The Musée Picasso continues here to show the richness of Picasso’s life and work. Don’t miss these two shows teeming with words and images.

Favorite