Overheard at the exhibition “Picasso Mania” at the Grand Palais: American man to American woman as he points to an erotic etching: “Do you recognize this?” Woman (looking bored): “No.” Man: “It’s on your breakfast plate every morning.”

The extent of Picasso’s influence – right down to the American breakfast table – is the subject of this entertaining exhibition full of works by other artists he inspired, along with some of his own.

The curators had a great idea for the first room of the exhibition: a large screen with a mosaic of video portraits of artists from around the

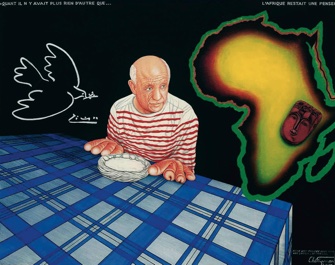

Seeing how different artists reacted to Picasso is great fun. Many made the man himself the center of their work. Chéri Samba satirizes Robert Doisneau’s famous photo of Picasso in his striped sailor’s jersey sitting at a table with “fingers” of bread in front of him. In Samba’s painted version (pictured at the top of this page) the fingers look more like penises in what I suppose is a nod to Picasso’s machismo. A map of Africa adorned with a mask floats in the background as reminder of the influence of African art on Picasso’s work.

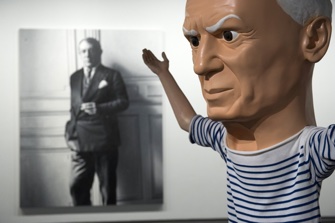

Maurizio Cattelan represents the artist in

Just as Picasso obsessively copied – in his own style, of course – the paintings of some of his predecessors, notably Velázquez’s “Las Meninas,” many of his successors have made their own versions of Picasso’s work. These take up the bulk of the show.

David Hockney worshipped at the altar of Picasso with his usual intellectual approach, always with a touch of humor. In his engraving “Artist and Model” (1973-74), the naked model is Hockney himself, sitting across a table from the master, who wears, naturally, a striped jersey.

Hockney also paid homage to Picasso with his “Cubist” technique of breaking up a scene by taking multiple Polaroids of it and then putting it back together again. Among the several Picasso-influenced works by Hockney in the show is “The Jugglers, 24 June 2012,” an installation of 18 synchronized videos paying tribute to “Parade,” the famous Ballets Russes production for which Picasso designed the costumes, set and curtains.

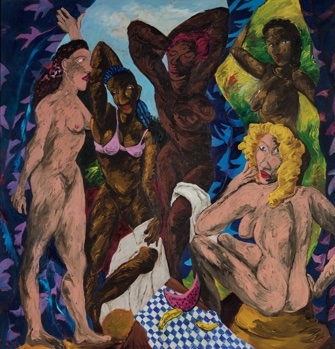

This exhibition, exceptional for its inclusiveness, shows the work of far more non-white, non-male, non-Western artists than we are used to seeing in blockbuster shows in major art institutions. African American

painter Robert H. Colescott (1925-2009) is represented by “Les Demoiselles d’Alabama (Des Nudas)” (1985), a wry take on Picasso’s 1907 African-inspired “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” In Colescott’s version, some of Picasso’s pink-skinned ladies are now black, which simply seems appropriate. (The label for this painting notes that Colescott was the first African-American artist to officially represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, at the shockingly late date of 1997.)

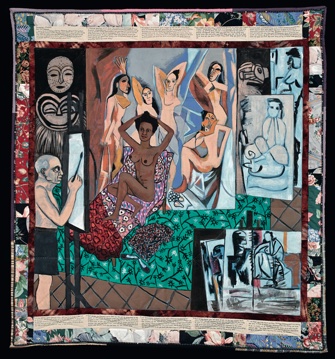

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” also figures in a 1991 painting by another African-American artist, Faith Ringgold (b. 1930). In “Picasso’s Studio” (from the series “The French Collection,” part I, # 7), the artist (shirtless this

A number of Picasso’s works are on show for comparison’s sake. Near the end of the exhibition, an entire wall of late paintings participates in a general movement to rehabilitate the reputation of Picasso’s later

works, which in the past had often been dismissed by critics as not up to the artist’s standards.

The list of artists represented in the show is long and impressive: Yan Pei-Ming, Paul McCarthy, Niki de Saint Phalle, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Louise Nevelson, Roy Lichtenstein and so on. And, while we may not all have Picasso’s erotic etchings on our breakfast plates, “Picasso Mania” beautifully demonstrates how his work has seeped into the collective consciousness of artists of every stripe.

Favorite