Until recently, all I knew about Clermont-Ferrand was that it was a place smack in the middle of France that one passed through on the way to other places and that it is the home of the Michelin tire company. Having stopped there for a mediocre dinner once during one road trip or another, I didn’t have a favorable impression of the place.

Like most French cities, however, Clermont-Ferrand has its charms, as I discovered when I went to its biannual Festival International des Textiles Extra Ordinaires in late September. One unique feature of the city is that many of the buildings in its center are made of black volcanic stone, most notably the Gothic Notre-Dame de l’Assomption cathedral, dramatically perched on top of a hill, its spires nearly reaching heaven.

This year’s textile festival is over, but a related, ongoing exhibition at the Musée Bargoin has takes up the same theme, “Rebels,” to show how textiles have been used historically and in different cultures in subversive ways or to support a cause.

Rebellion comes in many forms. The first section of the exhibition is about defying convention, illustrated by a work by Faig Ahmed, “Oiling,” (2012), a beautiful traditional Kazakh/Karachop carpet hanging on the wall

whose pattern seems to have gone wonky halfway through the weaving process, with the colors running down in rivulets. The title would indicate that it is also a commentary on the effects of the oil industry on traditional culture.

Political convictions can also be expressed through clothing. A display of simple, handwoven, hand-dyed dresses with timeless styles turn out to be made by a Kolkata-based company called Maku Textiles, run by members of the “slow fiber movement” who teach villagers to make homespun khadi-cloth products using traditional techniques, helping to improve local economies and continuing the struggle supported by Mahatma Gandhi, who refused to wear British-made cloth and tried to revive the Indian textile industry.

Sasha Nassar, a young Israeli fashion designer with a Muslim mother and Jewish father, uses clothing in a less-practical but more sensational way to express her views, dressing mannequins in see-through burkas, while artist Yara El-Sherbini dresses bowling pins up in head scarves to protest the way women are treated in Middle Eastern societies.

One exhibit – chilling and heartwarming at the same time – shows how textiles used for repression by the Nazi occupiers were turned into a protest device. A list of arrests in Paris on June 7, 1942, details infractions committed by “Aryans” who were “Friends of the Jews” wearing yellow cloth Jewish stars sewn onto their clothing in solidarity with the Jews who were forced to wear them. Some had written their first names on the stars or decorated them with embroidery, while an artist named Madeleine-Eugénie Bonnaire had not only wrongly worn a star but had dared to “thumb her nose at a group of German soldiers.” The newsseller Marie Lang had attached a paper star to her dog’s collar and ate the evidence when she was arrested. On display is the cloth star embroidered with her first name worn by 21-year-old Jenny Rion, who was punished with three months in a French internment camp.

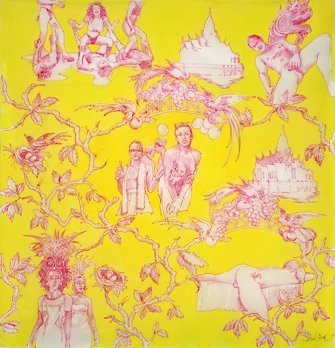

The examples of rebellion expressed through textiles goes on with surprising diversity: a Phrygian cap from the time of the French Revolution; paintings done on handkerchiefs by Mexican prisoners; Toile de Jouy by Jean-Ulrick Désert showing scenes from the

sex trade in Thailand rather than the usual pastoral images; and arpilleras, textile appliqués depicting folksy-looking scenes of violence or kidnappings, worn in Chile under the repressive Pinochet regime as a form of silent protest. Even Hermès gets into the act with silk foulards commissioned from artists to celebrate the bicentennial of the French Revolution.

This thoughtful and unusual exhibition is well worth a visit if you happen to be in the area of Clermont-Ferrand.

Favorite