|

|

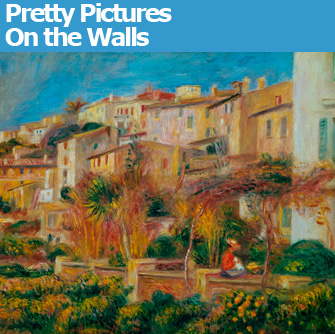

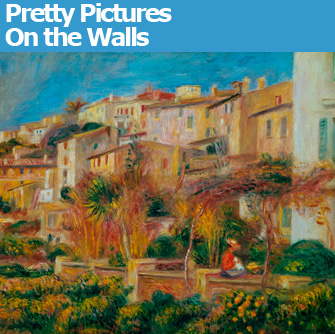

“Les Vignes à Cagnes” (1908). © Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Having OD’d on paintings by Renoir during a visit to the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia at the beginning of the year, I had trouble working up any excitement about visiting …

|

|

“Les Vignes à Cagnes” (1908). © Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Having OD’d on paintings by Renoir during a visit to the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia at the beginning of the year, I had trouble working up any excitement about visiting the new exhibition of his later work, “Renoir in the 20th Century,” at the Grand Palais, but I tried to keep an open mind, hoping to be pleasantly surprised and pleased by what I saw.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t. Looking at all those colorful, light-filled paintings of pretty, round women and children quickly grows tiresome. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) himself admitted that he thought painting should be decorative – something meant to “beautify” and “liven up the walls” – and that he tried to idealize his subjects, which may explain why they have such a saccharine quality.

This is the first retrospective to focus on the artist’s later period, after he had left Impressionism behind. During his last years, this affable man was crippled by arthritis yet continued to paint, concentrating on female nudes, portraits and studies of models, painting in what he considered a classical and decorative style.

Am I missing something? After all, many connoisseurs greatly admired Renoir. Poet Guillaume Apollinaire called him the “greatest living painter,” and Gertrude and Leo Stein, Alfred C. Barnes and many others collected his paintings. Gauguin managed to insult and compliment him in the same sentence: “Renoir is a painter who has never known how to draw yet draws well,” but Matisse called Renoir’s “Les Baigneuses” (1918-19) “the most beautiful nudes ever painted,” adding “No one has done better, no one.”

In this show, paintings by artists who took inspiration from Renoir – Picasso, Matisse and Bonnard among them – are shown alongside Renoir’s paintings of similar subjects. In almost every case, Renoir’s works suffer from the comparison. While the figures in Picasso’s “La Danse Villageoise,” for example, look strangely static next to the dancers caught in joyous movement in Renoir’s “Danse à la Campagne” (1883) and “Danse à la Ville” (1883), Picasso’s picture, in which the dancers’ staring eyes look away from each other, has a substance, mystery and intensity lacking in Renoir’s works.

Occasionally the vapid gaiety of Renoir’s canvasses is interrupted by a hint of something a little deeper: the woman in “Baigneuse Assise” (1914), for example, wears a melancholy expression and clenches her hand between her legs, while some of the portraits, like that of Paul Durand-Ruel (1910), an art dealer who bought over a thousand works from Renoir, successfully capture the individuality of their subjects in a way that the almost anonymous nudes don’t. The few landscapes included in this show are quite lovely.

A few years ago, I was captivated by a show of Renoir’s work at the Cinémathèque de Paris, exhibited in conjunction with images from films by his son, the brilliant director Jean Renoir. On reflection, I believe it was the careful selection of a small number of works, beautifully displayed, that made that show so appealing. Maybe Renoir should have stuck with Impressionism, a style that let him give free play to his talent for capturing light.

Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais: 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008 Paris. Métro: Champs-Elysées Clemenceau. Tel.: 01 44 13 17 17. Open Monday, Wednesday, Friday-Sunday, 10 a.m.-10 p.m.; Thursday, 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Closed Tuesday. Admission: €12. Through January 4. www.rmn.fr

© 2009 Paris Update

Reader Reaction

Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Favorite