We all take it for granted that when we go to the Louvre, Mona Lisa will be waiting for us, oblivious to her ridiculous situation as a very small painting hanging alone on a very big wall, cordoned off from the mob of tourists furiously snapping her image. In fact, it is something of a miracle that she is still there five centuries after she traveled to France from Italy in the company of her creator, Leonardo da Vinci. Since then she has survived a number of wars, the attacks of vandals and other catastrophes like being stolen in 1911 and taken back to Italy (a theft Picasso and his friend the poet Guillaume Apollinaire were suspected of committing, but that was actually the act of a former Louvre employee).

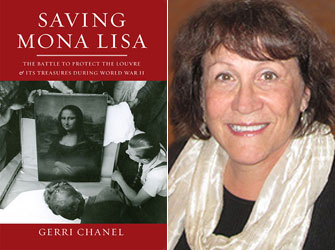

The story of how this fragile painting – and all the other treasures of the Louvre – survived World War II and the Nazi occupation is recounted in the recently published Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and Its Treasures During World War II, by Gerri Chanel.

I, for one, had never really thought about what happened to France’s precious art collection during the war, but, thankfully, Chanel did, and it is an exciting story that deserves to be told. Her curiosity was first aroused when she heard a tale about a painting being hidden in the ceiling of a café. It turned out to be apocryphal, but her research on it got her hooked on the subject.

The real story is that a gargantuan effort and years of planning went into the World War II art-protection effort, beginning as early as 1932.

The heroes of this story are Jacques Jaujard, director of the French National Museums and hence responsible for the Louvre (as of 1939), and his staff, many of whom risked their lives, health and comfort to ensure that the treasures of the Louvre and France’s other national museums would not be harmed by moving them out of Paris and into sites around the country less likely to be targeted in wartime, mostly in châteaux where storage conditions for fragile artworks were less than ideal. Moving, caring for, preserving and safeguarding them involved complicated logistics and management operations.

Many of the Louvre’s staff were active Resistance members, and the storage areas in the provinces as well as the Louvre itself were sometimes used to stockpile arms and print Resistance publications. Jaujard himself helped the Resistance when he could without endangering the art or the museum, and was something of a genius at evading German orders that would have put the art collection in jeopardy and at fighting the efforts of Hitler, Göring and Ribbentrop to get their clutches on treasures belonging to French museums, including the Bayeux Tapestry.

Jaujard also did what he could to protect the artworks looted from Jewish families by planting a spy in the Jeu de Paume, where they were stockpiled, namely the brave Rose Valland, heroine of the film Monuments Men, which told its own less-than-factual version of the tale.

In the end, Chanel writes, the Louvre and its artworks survived “gunfire, shells, bombs, damage from a crashed plane, fire and an enemy that wanted the museum’s treasures and in some cases came close to destroying them without a second thought.”

Chanel’s research is impressive, and she has written her eventful story with panache, keeping the reader hooked on the suspense, especially in the second half of the book. The first half, during which the artworks travel to their temporary homes, offers rather too much detail about the comings and goings of trucks and the difficulties involved in finding them and the fuel to run them on, but that is all part of a story that is worth telling and that Chanel has recounted so well.

The next time you visit the Louvre, spare a thought for those who helped save its artworks and give thanks that Mona, Venus and Victory and their many companions are still there.

Favorite