Lucky students at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts! Not only do they get to study and make art in beautiful historic buildings in the heart of Saint Germain-des-Prés – now rather dilapidated, it’s true, but that only adds to their charm – on a campus in the heart of Saint Germain-des-Prés, but they are surrounded by masterful copies of sculptures and paintings of art through the ages, mostly made in the 19th century by expert Italian copyists.

Those copies have inspired an entertaining temporary exhibition, “Sculptures Infinies: Des Collections de Moulage à l’Ère Digitale” (“Infinite Sculpture: From the Antique Cast to the 3D Scan”).

The 16 contemporary artists involved, all of whom use casting in their work in one way or another, had free run not only of the Beaux-Arts’ collection of plaster casts but also those of the Louvre (stored in the stables of the Château de Versailles), the Grand Palais and the Faculdade de Belas-Artes in Lisbon (the Portuguese city’s Calouste Gulbenkian Museum is a partner in this endeavor, and the exhibition will be shown there after its Paris run).

Upon entering the show, in two grand halls in the Beaux-Arts’ 19th-century building on the Quai Malaquais, one’s senses are confounded by the sight of so many familiar-looking antique sculptures accompanied by their strange contemporary partners, some of which seem to echo them and others to mock them.

Stephen Claydon’s “Voyager Assembly” (2016), for example, is based on a cast of a Roman statue, “Old Fisherman, or Dying Seneca.” Claydon projects the antique sculpture into the future in his version by replacing the top part of the head with a frightening cast of the head of the villain played by Wesley Snipes in the 1993 science-fiction film Demolition Man, separating the blue-painted body from the head with a plate of glass.

In the basement of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Christine Borland, a Scottish artist, came across a cast of a dissected corpse, posed in the same position as Christ in Michelangelo’s Pietà, which had been used as a teaching model for medical students. She made two casts of this disturbing piece, with its skin partially sliced and peeled back, and posed them horizontally, with one facing upward and the other downward. The latter seems to be in flight: a macabre angel with a strange, Joker-like smile.

Similarly, each piece in the show has many layers of meaning. Since there are no labels, you won’t be able to figure out what is what and which contemporary artist did which pieces without referring to the booklet available at the beginning of the show (available in English).

During the press visit to the exhibition, the journalists were allowed to visit some of the school’s usually private areas: the beautiful 17th-century chapel, left behind by the Petits-Augustins Convent, founded par Marguerite de Valois, which used to occupy the site, and the Atelier de Morphologie.

On the way, we passed through an Italianate courtyard (pictured at the top of the page) and, in a hallway, an antique dissecting table (dissections used to be performed at the school) recently discovered by a student.

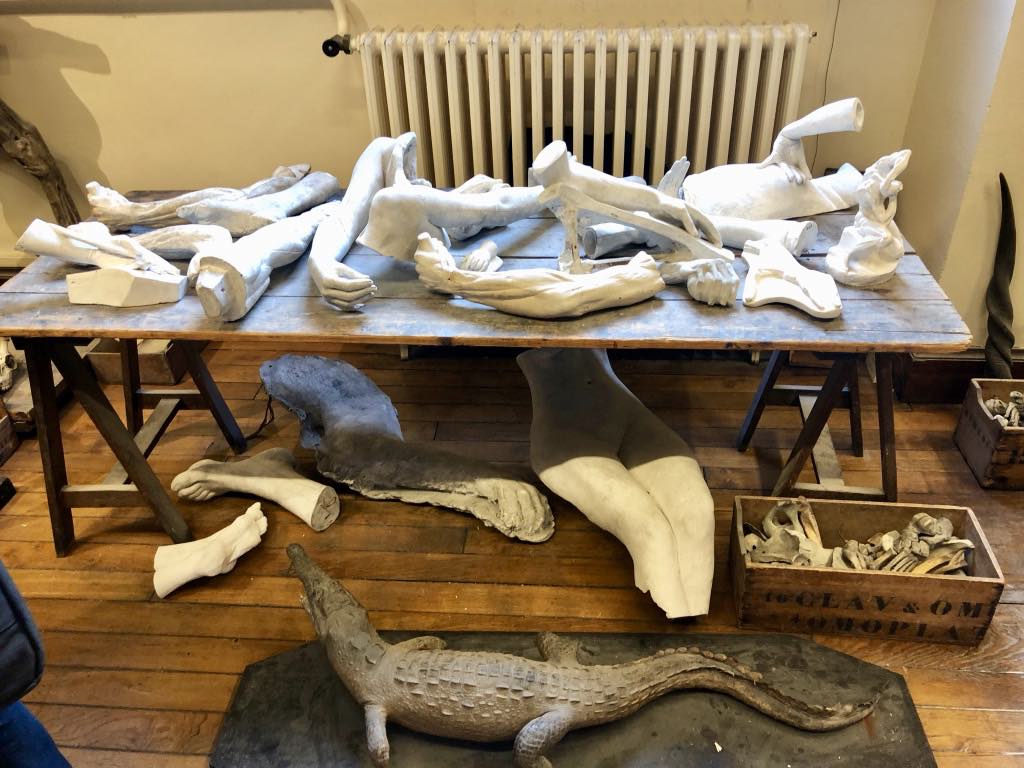

The chapel is filled with plaster casts (one side chapel features works by Michelangelo) and copies of paintings, while the Atelier de Morphologie is crammed full of casts of skeletons and dissected animals.

This inventive show honors the arts of antiquity while giving today’s artists a chance to express their fears and fancies. It’s most interesting to see how the purely representative art of the past has been conceptually reinterpreted for our current concerns.

Favorite