Painting takes flight from the traditional flat canvas on a stretcher in the two current exhibitions at Fondation Louis Vuitton. Upstairs, the works of the five artists featured in “Fugues in Color“ interact with the high-ceilinged, light-filled, oddly shaped galleries, while a major retrospective of the work of Simon Hantaï on the occasion of the centenary of his birth is presented on the lower floors.

Hantaï (1922-2008) was a Hungarian artist who settled in Paris in 1948 and stayed, eventually becoming a French citizen and a major figure on the art scene. One of his early inspirations was the work of Jackson Pollock, an influence that is explored at the beginning of the show. He also joined up with the Surrealists for a few years but took his leave in 1955.

By the end of the 1950s, the artist had moved in a new direction as he left figuration behind completely and set out to liberate painting from its flat surface by using canvas that had been crumpled or folded. I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that he became obsessed with this procedure. Over the following decades, he produced numerous series of works exploring variations on the folding technique, each with its own distinctive look.

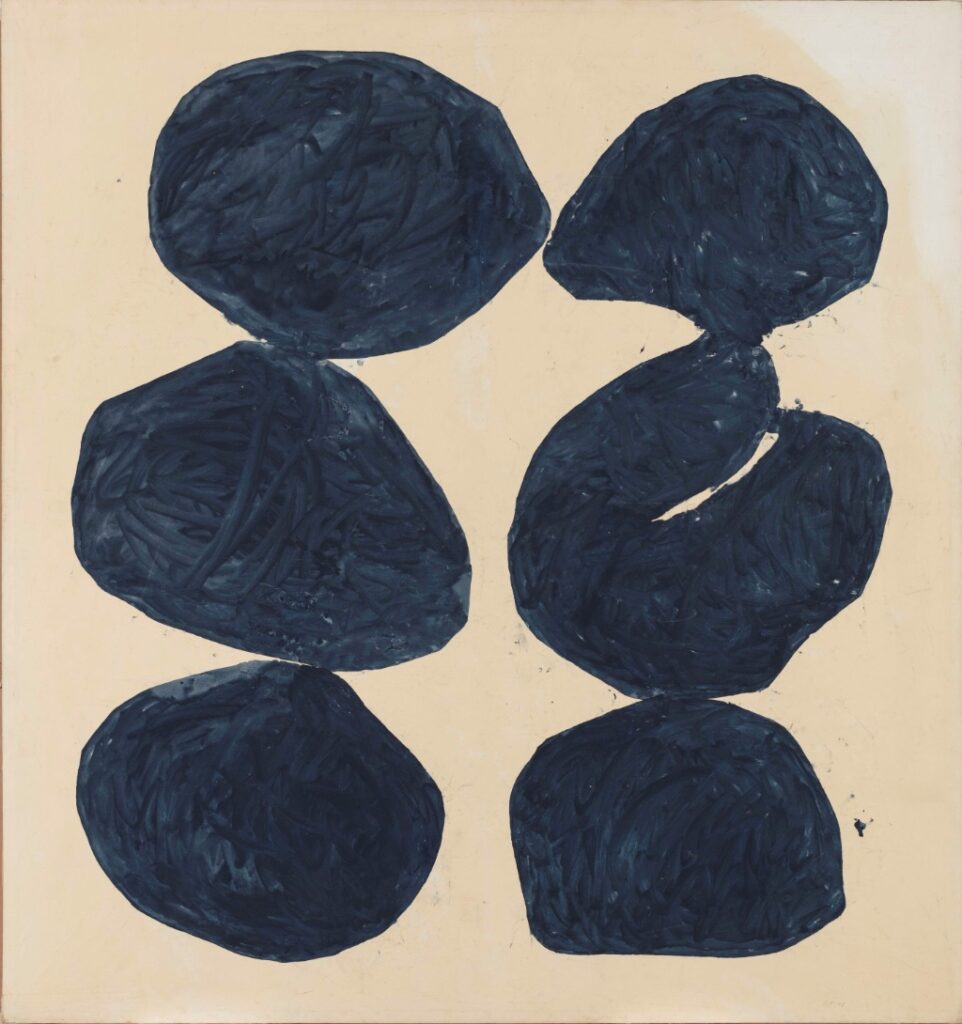

In the “Marians” series (1960–62), with its mystical underpinning related to the Virgin Mary, he created relief by crumbling the canvas, but then tried to re-flatten it. In the “Catamurons” series (1963–65), the forms start to take on a life of their own as the white canvas is allowed to reveal itself, a trend continued and expanded in the “Meuns” (1967–68) series, which calls to mind the late-life cutouts of another artist who was an influence, Henri Matisse, and in the “Paunches“ series (19 64–67), in which the larvae-like forms seem about to explode into life.

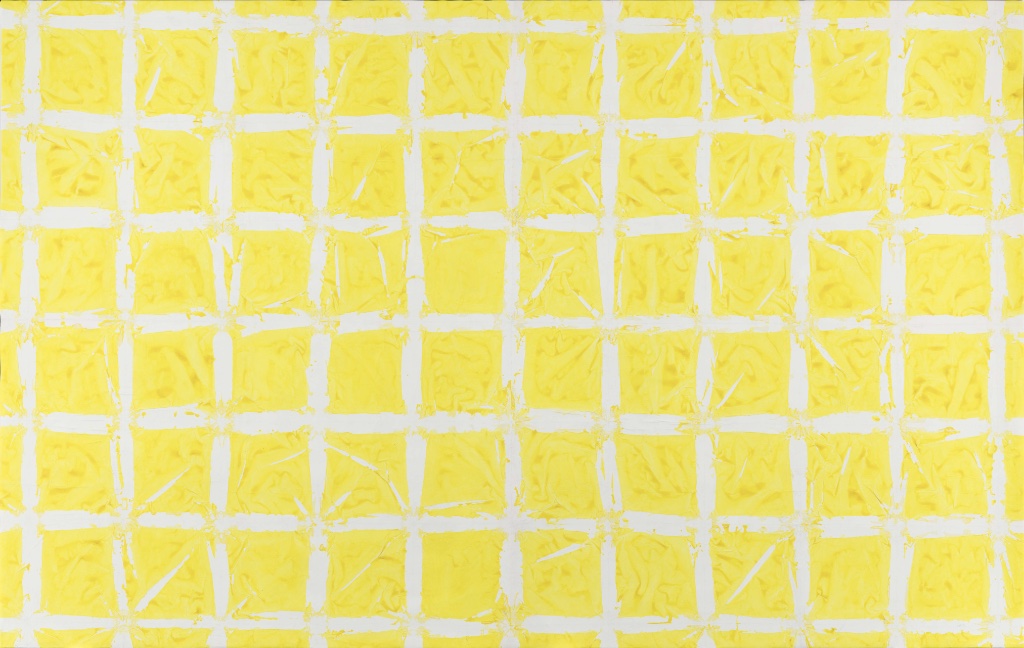

The shapes and colors changed again in later series like “Studies” (1968–71) and “Whites” (1973–75), before color theory came to dominate his work with the “Tabulas” (1972–82), monumental canvases with squares of pure color reminiscent of the color experiments of Josef Albers. These paintings are presented in a large space that positively vibrates with their bright hues. By 1982, however, he had basically renounced color in the white/off-white series “Lilac Tabulas,” “Shrouds” and “Mists.”

In 1982, Hantaï announced that he would stop painting. In fact, he stopped showing his work, but he did not stop working, making what the curators call “drip-fold” paintings, in which the drips come out of the folds (Pollock was still on his mind). He also turned his studio into what might be called an all-over work of art as he attacked previous works, tearing, painting on, layering and gluing them until they became veritable sculptures. The final room of the exhibition re-creates in part this amazing “Last Studio.”

To get an idea of Hantaï’s dedication to his work, look at the film in which he shows how the “Tabulas” were made, a process of hard labor that leaves the artist sweating and panting after wrestling with an enormous canvas on the floor as he knots and paints it.

Upstairs in the foundation’s spectacular Frank Gehry building, the monumental installations in “Fugues in Color“ echo beautifully with the Hantaï exhibition in their refusal to paint in the traditional way.

Entering the first gallery is like walking out of a darkroom straight into a dazzling sunny day. You can’t help but feel immediately uplifted by Megan Rooney’s “With Sun” (a detail is pictured at the top of this page), painted directly onto the walls of the room in a wild dance of vibrant color (mostly yellow, orange and pink, with touches of blue and purple) that reaches all the way up to the skylight. The real sun plays its own role, casting light on different parts of the work, depending on what time you visit.

There is a story behind this site-specific work. Says Rooney: “When I was lying on the floor of the gallery, staring into the sky through the open portal in the ceiling above, I began to dream a little story. The moon chases the sun through the building. She slips down the aperture in the ceiling and gets trapped bouncing around the room.”

Painting gets deconstructed in a different way by Sam Gilliam’s “Carousel Merge” (1971), three gigantic unstretched canvases, beautifully painted in a wealth of colors, hanging like sheets on a laundry line. The works by Steven Parrino, like Hantaï’s, crumple and fold the canvas, creating sculptural pieces, while Niele Toronto’s simple polka-dot paintings come in many shapes and sizes, adapting to the room they are shown in, even fitting into a corner.

Much more dramatic is Katharina Grosse’s room-sized installation “Splinter” (2022), covering the walls, floor and ceiling in screaming loops of color. Grosse is working on another monumental site-specific piece commissioned by the foundation, “Canyon,” which will be installed in September. A model of what promises to be a sensational work is on show in the stairway next to the galleries.

Favorite