The Manly Art of

Portraying Prostitution

“Rolla” (1878), by Henri Gervex. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

Oscillations in representations of prostitution are almost as violent as the hazards of the profession itself. The exhibition “Splendour and Misery: Pictures of Prostitution in France (1850-1910)” at the Musée d’Orsay is the first to examine the ambiguous role of the prostitute – a source of inspiration, adoration and revulsion – in society. It variously shows us streetwalkers prowling the shadows in pursuit of prey, a swarm of Eurydices condemned to an eternity in the underworld of the gutter, and the Venuses of aristocratic drawing rooms, honey traps spinning viscid webs for their patrons.

In tracing the fluctuations between the fascination and repulsion associated with what is famously the “world’s oldest profession,” the Musée d’Orsay aims to offer visitors insight into French society and morality during the late 19th century. Works by both French and international artists in a variety of media – painting, “salon art,” photography, decorative arts and sculpture – provide a showcase of the people and places associated with prostitution to illustrate, in vivid brushstrokes, the seedy underbelly of a supposedly refined and modern nation.

The hedonistic, promiscuous female inhabitants of the demimonde had an ambiguous position in French society as fashionable figures nonetheless exiled to its fringes by the “courtesan” label. The “splendour” of the exhibition’s title refers to the dazzling color, sumptuous clothing, regal posture and voluptuous representation of

“Madame Valtesse de la Bigne” (1879), by Henri Gervex. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski

these women in paintings like Charles Emile Auguste Durant’s 1876 “Portrait de Julia Tahl, dite Mademoiselle Alice de Lancey.”

Opulent decorative pieces that furnished the homes of these women also reveal the extraordinary wealth they were able to amass. An ebony cabinet dating from 1865, adorned with enamel, ivory and lapis lazuli, was commissioned by Thérèse Lachmann, one of the richest French courtesans of the 19th century. The cabinet’s identical twin was shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle, testament to its spectacular design as well as the public fascination with its fabulously wealthy demimondaine owner.

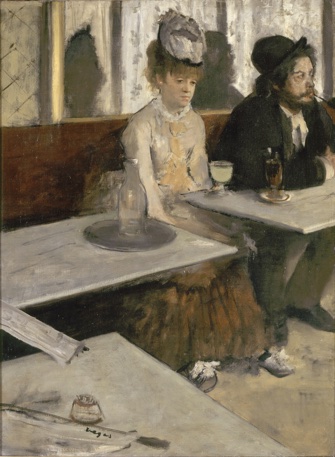

The “misery” is epitomized by Degas’ “L’Absinthe” (1875-76). The female subject’s sallow complexion and downcast gaze, and the male figure’s complete disregard for his companion express her extreme isolation. A

“L’Absinthe” (1875-76), by Edgar Degas. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

diffuse light source coming from outside our field of vision leaves inky shadows etched on the wall and does little to efface the bleakness of the scene. Haphazard framing, which cuts off part of the man’s arm and the objects on the table, evokes a drunken swaying sensation, as does the noxious liquid standing on the table: the absinthe of the work’s title. The overwhelming desolation of this painting led critics to denounce it as vile and ugly from its very first showing.

Masterpieces by the likes of Manet, Picasso and Cézanne sketch out the evolution of modern art and the centrality of prostitution and prostitutes to this development. The contrasts in Picasso’s depiction of prostitutes in the exhibition, for instance, provide visitors with an overview of the artist’s own stylistic development. The vibrant caricatures in “Nu au Bas Rouges” morph into ashy, pastel figures in such images from his blue phase as “Femme Assise au Fichu (La Mélancolie)” and are brutally reduced to primitive forms during his exploration of Cubism. He captures every angle of the life of prostitutes: merry vessels of pleasure, bleak figures with lost souls and uncivilized facilitators of carnal need.

By its very nature, prostitution transforms the female body into an object of public pleasure, and the influence of these enigmatic female figures on all the arts is also reflected in extracts of literary masterpieces, famous songs and celebrated plays scattered throughout the exhibition in quotes or physical form.

The fascinating history and daily life of prostitutes are also depicted in stark, realistic documentaries and films that plunge visitors into an underworld of shadows, red lights and daily debauchery. Medical photographs and scientific accounts reveal the sickening reality of venereal disease, abuse and infection faced by women auctioning their bodies off to the highest bidder.

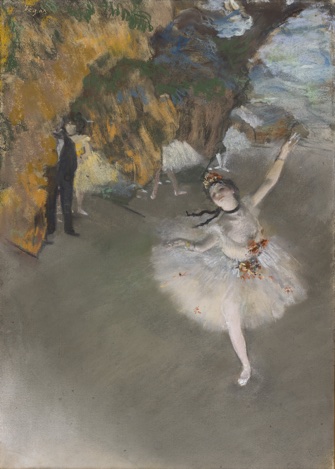

The economic facet of this life is explored in paintings with ballet and opera themes. Degas’s “Ballet (L’Etoile),” completed around 1876, depicts a young dancer on stage. She seems to be swept up in the emotion of her performance, and everything from her blissful expression to her pearlescent skin is radiant, celestial. Her snowy, youthful flesh stands in stark contrast to the shady background, where

“Ballet (L’Étoile)” (c. 1876), by Edgar Degas © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Patrice Schmidt

a dark figure, a raven-clad man, lurks. Degas thus illustrates the way rich men used financial support as a means of exploiting young actresses, dancers and other performers. The variations in tone, from virtuous white to obsidian black, are a clear denunciation of such sexual subjugation.

In fact, what emerges most vividly from the exhibition is this theme of the manipulation of women by men. “Splendor and Misery” may well be an exploration of the figure of the prostitute, but it is an exploration conducted by male artists. Whether the prostitute evokes adoration in her all her splendor or revulsion in her misery, it is men who are the interpreters. Each female figure suffers a certain amount of vulnerability in being left open to portrayal through the prism of the male gaze – most apparent in the raw exposure of their naked form. The more contemporary sections of the exhibition demonstrate how, with the advent of the art of photography, women became, more than ever, objects to be placed, styled, distorted and controlled by men.

Musée d’Orsay: 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007 Paris. Métro: Solferino. RER: Musée d’Orsay. Tel.: 01 40 49 48 14. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30 a.m.-6 p.m., until 9:45 p.m. on Thursday. Closed Monday and Christmas Day. Admission: €11. Through January 17, 2016. www.musee-orsay.fr

Reader reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2015 Paris Update

Favorite