The life of Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938) is the stuff of Montmartre legend. An artist’s model, she got pregnant at the age of 18, father unknown (as was her own). An artist friend, Miguel Utrillo, agreed to give his name to her baby, Maurice (1883-1955), who became the famous painter of Montmartre street scenes and a notorious Montmartre drunk. One night, a friend of his, an electrician and budding painter named André Utter, scraped him up from the gutter and took him home to his mother. A new human triangle was born as Valadon fell in love with Utter, 21 years her junior. That triangle is the subject of the exhibition “Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo, André Utter” at the Musée de Montmartre.

Valadon had learned to paint by observing the techniques of the leading artists she modeled for, among them Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes and Edgar Degas. It was Degas who encouraged her most as an artist, teaching her new techniques, buying some of her work and giving her the ultimate accolade: “You’re one of us.”

The exhibition focuses on the 14 years the three artists lived and worked together, from 1912 to ’26, at 12, rue Cortot in Montmartre, which just happens to be the site of the Musée de Montmartre itself (don’t leave without visiting the restored living quarters and studio on the top floor and, of course, the lovely garden).

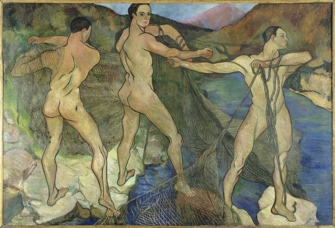

It is heartening to learn that Valadon had quite a bit of success in her lifetime, even though she was a woman working in a man’s field and, even more unusual at the time, a woman painting nudes, mostly of women. A notable exception is the wonderful 1914 “Le Lancement du Filet,” or “Casting the Net,” a veritable celebration of the male body, with Utter the model for all three of the heroic male nudes.

One of the most fascinating paintings in the show is “The Future Unveiled, or the Fortune Teller” (1912), which features a monumental female nude stretched out on a red sofa (the original couch can be seen upstairs in the living quarters), while the much smaller, fully clothed figure of the fortuneteller kneels on a Persian carpet on the floor beside her reading her cards. The naked woman’s pose has nothing of the come-hither sexiness of, say, Manet’s “Olympia” (1863); it is a man’s pose, confident and open, domineering, as she looks down haughtily at the little woman on the floor.

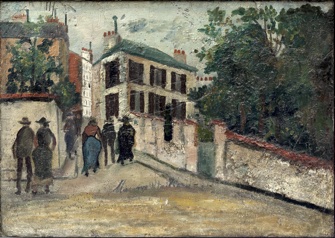

In spite of her success, however, Valladon seems to have been overshadowed after her death by her son, whose paintings of Montmartre, which he rarely left, are iconic. In fact, he seldom even left home except to drink (he was mocked in the neighborhood as “Litrillo” because he was capable of drinking liters of wine); many of his paintings were based on postcard images. The quality of his work deteriorated as he grew older and more alcoholic, but many of the earlier ones show the talent that later went to waste.

Valadon and Utter were also talented painters whose works exhibit great, almost (but not quite) naive charm without being terribly original. Valadon liked to outline her figures with a black line, and some of her early works on paper, like “Christiane” (1905), with its awkward shading and stiff figure, look a tad amateurish but are still winning. Utter’s paintings, from what can be seen here, are uneven but can be quite powerful; examples are his portrait of a hulking, red-nosed Utrillo and his self-portrait with a turban wrapped around his head.

One of the most touching stories recounted in the exhibition concerns another of Valladon’s lovers, Erik Satie (1866-1925), shown here in a lively, colorful portrait by Valadon. With his big black hat, long hair, beard, curly mustache and wire-rimmed glasses, he looks like an eccentric bohemian. The 26-year-old composer was mad about his “Biqui,” as he called her, but she dumped him after six months, and he apparently never had another love.

As for Valadon and Utter, their love affair (and marriage) eventually ended, and she and Utrillo moved out of 12, rue Cortot in 1926. They stayed in touch, however, until her death in 1938.

If you love Paris, you have to love Montmartre, and if you love Montmartre, you have to see this show.

Favorite