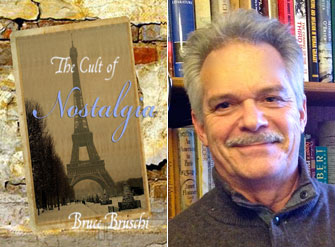

In the “Quatrième Partie” of The Cult of Nostalgia, Bruce Bruschi’s elegiac first novel, the heroine, Carly, an American in Paris, comes to a cutting realization. Left by a lover of seven years, she suddenly faces his lack of feeling for her. As the narrative has it: “What they had been together was apparently something only she had imagined.”

This witty novel of love and misperception begins in a bookshop in San Francisco, a space so gloriously realized you feel you can see every picture on the wall. Here Carly meets Simon, the lover who leaves her, and at the same time immerses herself in his love for Paris. Bruschi nods to Proust as he writes of Simon: “He had always felt nostalgia for Paris, he explained that first time they spoke, even though he had never been there.”

If this is a novel about love, it is in particular a novel about love for Paris and the sway the city has held for so long over the American imagination. This theme is orchestrated brilliantly across three gradually converging storylines tracing moments of encounter in the city in 1925, 1963 and Carly’s present 2003.

The 1925 sequences take the form of memoirs written by Edward Stephens, an American academic reliving his love affair with the Left Bank. In this strand, Bruschi gradually calls to life some of those literary figures whose exile in Paris in the interwar years has proved so legendary, among them Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Ernest and Hadley Hemingway, and Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. These are some of the most graceful passages in the novel, in which Bruschi’s imagination, humanity, open-mindedness and humor come to the fore. I believed utterly in his characters, even those based on historical figures, and this delicacy and lifelikeness makes the different versions of established stories the more riotous. Bruschi is attuned to the ways we all make up stories about each other and uses this skill deftly to offer his own version of the story of Hemingway and his lovers.

There’s something compulsive about reading The Cult of Nostalgia and following through its different stories. The luxurious intensity of feeling is usually inspired by Paris itself: “Not suddenly, like creative inspiration, nor reasonably, like scientific deduction, nor irrationally, like love or fear or passion or sorrow does the notion come upon you that soon you will be leaving Paris. It is an eventual thing, a lingering predisposition, subtle as a change of seasons and as unspecific as the inception of dusk.”

For all the wistfulness of passages like that, this is a very funny book, with a touch of Armistead Maupin’s hilarity and through it all a deep vein of compassion. Bruschi has expanded the narratives of literary Paris, tenderly mapping its stories of love and longing. The end made me cry, with happiness.

Favorite