If you say the word “France” to people, they immediately think of looking up women’s skirts. And there’s a perfectly good, logical reason for this: the people you happened to pick are all testosterone-addled straight guys, who never think about anything else. You could have said “France,” “Tajikistan,” “Antarctica” or even “prestressed concrete” and they’d still have thought about looking up skirts. Next time try some women or gay men — someone with at least a modicum of sense.

But it’s too late now. And the situation is not helped any by the existence of the can-can.

The can-can is, of course, a dance. Like most immortal classic dances, including the waltz, the tango, the hokey-pokey and the Paris-sidewalk-before-the-pooper-scooper-law, it was not created all at once but developed gradually over many years.

The roots of the can-can date back to the 1830s, when groups of young men would crowd the nightclubs of Paris and dance in an unbridled, rowdy fashion, flailing their arms and legs about like the Wizard of Oz scarecrow in a wind tunnel.

The dancers were called chahuteurs (“jerks”), and the dance was called the “can-someone-please-get-the-bouncer-to-kick-these-jerks-out-of-here-on-their-collective-can?” This was later shortened to “can-can.”

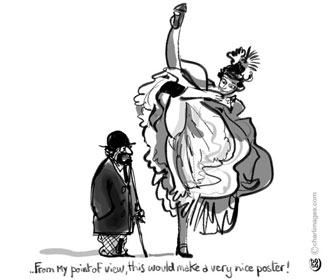

As the century progressed, and modesty regressed, the can-can became more widely practiced by women. By the 1880s, it had evolved into a dance based almost entirely on high kicks that would flip up the dancers’ long voluminous skirts to reveal their long voluminous petticoats and, in a good light, their legs. Which were also in many cases long and voluminous, but no matter what their morphology were a rare and titillating sight by late-19th-century standards.

Based as it was on keeping the legs airborne and therefore visible as much as possible, the can-can required considerable flexibility, training and stamina. For this reason, there were relatively few people who could (and were willing to) do it well, but, due to the above-mentioned rarity-titillation factor, there were a great many people (i.e., testosterone-addled straight guys) who were willing to pay money to watch them do it.

For this reason, the nightclubs started hiring can-can dancers to lure in the clientele. Then they started installing stages and spotlights to make it easier for a greater number of droolers, I mean spectators, to ogle, I mean watch, the exhibitionists, I mean dancers.

And thus the simple Parisian dance hall evolved into the elaborate, expensive Parisian music hall. The most popular of these droolpits back then, and now, was the Moulin Rouge in Montmartre.

As everyone knows, moulin rouge means “red mill,” and the nightclub stands on a site where a red windmill used to be. But as few people know, moulin rouge actually means, “We made this up out of whole cloth for the purposes of shameless, bald-faced commercial hype,” and the nightclub stands on a site where a nightclub used to be.

When it was opened in 1889, the most successful dance halls in Paris were the Moulin de la Galette (which really was a windmill and is still there, at the corner of Rues Lepic and Girardon) and the Château Rouge (which really was red but not exactly a castle and is not still there, but its memory lives on in the name of a non-red and decidedly non-palatial Métro station).

After cobbling together a trendy-sounding trade name, the founders of the Moulin Rouge pieced together a troupe of the finest can-can dancers in town, including such illustrious names from the annals of the terpsichorean art as La Môme Fromage (“The Cheese Kid”), Nini Pattes en l’Air (“Nini Limbs Aloft”), Pomme d’Amour (“Candy Apple”), Grille d’Egout (“Sewer Grate,” so-called as a metaphor for her teeth, because they were widely spaced and most commonly seen, at least by her gentleman friends, in a horizontal position from above) and Rayon d’Or (“Golden Synthetic Fabric”), who was later kicked out of the chorus line for failure to have a sluttier nickname.

But two of the dancers stood out in the public imagination, and, as a result, in the famous posters by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and, as a result, in the history of the can-can, and, as a result, in the cultural history of France, and, as a result, in this very long sentence, which is not over yet: Jane Avril (a.k.a. La Mélinite, named after an explosive), and the most outstanding and upkicking of them all, La Goulue (“The Glutton,” so-called for her habit of draining customers’ half-empty glasses).

La Goulue’s parents and grade-school teachers called her Louise Weber. The daughter of a washerwoman, she got her start as a dancer in her teens, when she developed the habit of borrowing the fancier outfits from her mother’s in bin to go out on the town at night.

As it turned out, Mademoiselle Weber possessed just the right subtle, alchemical combination of agility and depravity needed to make a good can-can dancer, and, after reaching adulthood and returning most of those borrowed dresses, she was hired by the Moulin Rouge.

Her act is immortalized in what is perhaps Toulouse-Lautrec’s best-known poster:

For those who prefer photorealism to Postimpressionism, here’s what she actually looked like:

At the peak of her fame and flexibility (both physical and moral), La Goulue wowed ’em at the Moulin every night, adding such refinements to her act as kicking men’s hats off and embroidering a heart on the backside of her bloomers so that spectators would know where to look when she hoisted her skirt from behind.

By 1895, La Goulue was rich and famous, the star of Montmartre and the pain grillé of Paris, with the world at her feet. Or legs. But, like any given glimpse of her garters, it didn’t last long.

Apparently seeking to set a precedent for the future careers of David Caruso and David Lee Roth, Ms. Weber decided to leave the Moulin Rouge and tour the country with her own show. The venture was about as successful as New Coke and, combined with a few ill-advised investments, left her centimeless.

It was not a good time for her to run out of money, because, of course, can-can dancing, like fashion modeling, Olympic hurdling and perceiving the utility of Google Glass, is an activity for the young. And so, as La Goulue entered middle age she found herself in reduced circumstances.

Unfortunately, her circumstances did not re-expand between then and the onset of old age, and the erstwhile queen of the Parisian night ended her days living in a trailer parked on Boulevard de Clichy, within jeté-ing distance of the club where she used to reign with an iron ankle.

There she scratched out a subsistence selling peanuts and cigarettes to passers-by, signing the occasional autograph and, I suppose, flashing the occasional bit of crinoline for old times’ (and old-timers’) sake.

She died in 1929 and lay in rest in an obscure suburban cemetery until 1992, when there was a renewal of interest in her legend and legacy. La Goulue’s remains were transferred to Montmartre Cemetery and placed under a new headstone in a ceremony attended by then-Moulin Rouge headliner La Toya Jackson. Who thus became the first, but not last, member of her family to appreciate the PR value of an intentional wardrobe malfunction.

Lowly beginnings, a rise in the public eye, a short age of glory, a long period of decline and finally enshrinement as a national icon: the history of the can-can itself followed the same trajectory as the life story of its most fabled practitioner.

At first disparaged as a lewd, vulgar spectacle, the dance enjoyed wild popularity around the turn of the 20th century. Then after World War I it was overshadowed by new rhythmic pastimes like the Charleston and remained an intermittent memory until it was revived in the early 1960s, most notably in a Moulin Rouge revue.

The skirts rose again, both literally and figuratively, and the can-can is now seen as a symbol of French identity, on a par with the beret, the poodle clipper, the transit strike and that big curvy, pointy metal thing that sticks up over the Paris skyline.

To reflect the dance’s emblematic status, every show at the Moulin Rouge today features a rousing can-can number, usually with the dancers decked out in blue, white and/or red to evoke the colors of the French flag. Of course, these are also the colors of the American, British, Chilean, Costa Rican, Croatian, Cuban, Czech, Dominican, Dutch, Icelandic, Laotian, Norwegian, Panamanian, Paraguayan, Russian, Serbian, Slovakian, Slovenian, South Korean, Taiwanese and Thai flags.

But hey — around here, when you look up women’s skirts you’re supposed to think of the word “France.”

Note: this article was originally published on December 2, 2013.

© 2013 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.