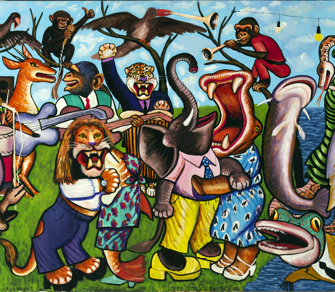

In these days of YouTube kittens and DreamWorks penguins, contemporary representations of animals often skew cute or decorative. The eye-catching poster seen all over Paris hyping the Fondation Cartier’s new exhibition, “The Great Animal Orchestra,” seemed to be a case in point with its illustration of a band of fauna – a gazelle on guitar, a cheetah on drums, etc. – whose jungle jiving is causing a throng of gaudily attired African wildlife to get their groove on.

Painted by Congolese artist Moke, “L’Orchestre dans la Forêt” is one of several vividly hued, large-scale canvases displayed on the main floor of the Fondation Cartier, alongside similar works depicting wild bohemian animal-musicians by his contemporaries Pierre Bodo and JP Mika. In isolation, their appeal is fun and fanciful. Just as fantastical, however, are the real-life antics of New Guinea birds of paradise being shown on a nearby row of “aviary videos” filmed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. In the feverish throes of courtship, avian alpha males are caught tweeting operatically, puffing up their plumage, and executing Astaire-worthy choreographies. The real birds and their imaginary painted cohorts all seem to be jamming together in one big delirious jamboree.

The dynamic interplay between these works – and these animals – effortlessly overrode my initial “cute” and “decorative” misgivings. As I continued around the main floor, feral riffs and refrains produced by some 20 artists from around the world began to lodge in my brain like visual earworms.

A series of slide shows created by Manabu Miyazaki struck a strange and dreamy chord. Using a robotic motion-activated “camera

trap,” the Japanese artist succeeds in voyeuristically capturing private moments in the day and night life of birds, animals, and even trespassing humans on the move in the wilderness.

On an equally lyrical but more somber note is the vast 18-meter-long mural created by Chinese artist Cai Guo-Quiang, which depicts a Noah’s Ark of animals gathered around a watering hole. This harmonious portrait is laced with uneasy tension. Not only do the

drinking buddies consist of natural predators and prey, but the drawing was created with gunpowder, which (as shown in an accompanying making-of video) was set alight in order to create the final smoke- and burn-smudged work. In these antagonistic days of Trump and Brexit, Guo-Quiang’s utopian vision ironically underscores wild beasts’ more civilized stance.

Displayed in the Fondation Cartier’s light-suffused “glass-house” building, the works on the main floor benefit enormously from the Arcadian forest backdrop of the garden surrounding it. The contrast is striking when visitors descend into the dark basement and are confronted with the show’s crux: the work of American musician, ecologist and bioacoustician, Bernie Krause.

During the 1960s and ’70s, Krause performed as a musician with the likes of Van Morrison and The Doors and scored such legendary films as Apocalypse Now. Then, in the ’80s, he turned his back on music created by humans and began focusing on recording the amazing vocal solos and choruses performed by animals on land and sea around the globe.

In the last 40 years, Krause has racked up some 5,000 hours worth of recordings of the buzzing, tweeting, humming, and howling of 15,000 species. A Best Of sampling can be experienced in a darkened room where visitors can sprawl on comfy space-age cushions on the floor and listen for hours, if they so wish, to the orchestral movements believed to be the precursors to human speech – and song.

The English collective United Visual Artists (UVA) has created the accompanying electronic installation, which translates Krause’s seven soundscapes into neon-colored waves of light projected onto the walls. However, it’s actually more primal and powerful to simply close your eyes and let the chaotic jumble of shrieks and roars magically morph into a precise musical score recorded live in Algonquin Park or the Amazon Rainforest.

Equally stirring, and sobering, is learning that since Krause began his pioneering work in biophony, close to half the voices he’s recorded have gone silent. Although we are aware that we’re destroying our natural landscapes, we’re deaf to the fact that we’re obliterating our soundscapes as well.

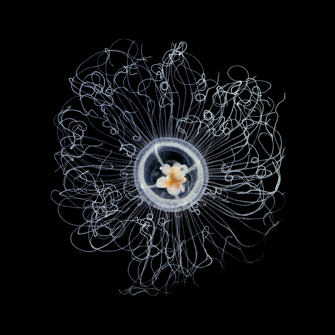

And how would silence sound? A final installation focusing on plankton offers a surprisingly poetic suggestion. Microscopic plankton, the source of all life on earth, make up 98 percent of the oceans’ biomass. This seems even more amazing when you

contemplate the still and moving images created by Japanese artist Shiro Takatani based on photos taken by French scientist Christian Sardet. Magnified exponentially, these invisible creatures are as otherworldly as Star Wars extras and as iridescently beautiful as Boucheron bling. It’s a fitting, and strangely uplifting, finale to the exhibit.

Happily, there is an encore for those who wander into the Fondation’s garden and into a rustic wooden shack. Inside, a mound of earth and a video screen are part of an installation created by French filmmaker Agnès Varda in homage to her dear departed cat Zgougou. After the multiplicity of voices and wild and worldly strains of The Great Animal Orchestra, this tender tribute to a domestic pet offers an intimate end note that lingers on.

Favorite