A few weeks back, I wrote about how Nancy and I found our first rental apartment in Paris, a saga that involved frequent repetition of the phrase “We were so lucky!” I called that article “The Luck of the Draw, Part One” because in parallel with apartment hunting I had another ordeal to deal with at the time, also rather reliant on luck: becoming a legal resident of France.

Like every other country worth living in, France requires would-be foreign residents to show proof of a number of attributes, including:

1) A permanent address,

2) A lack of a criminal record,

3) A job and/or enough money to support themselves, and…

4) The capacity to endure torrents of humiliation.

Before I go on, I must point out that immigrating to France has become much more applicant-friendly since I first moved here. Furthermore, as far as I know, it is easier for an American to become a legal resident of France than for a French citizen to emigrate to the United States.

But back to my list: attribute no. 4 is not exactly specified in the constitution, but tends to emerge as part of the procedure for demonstrating attributes 1 to 3. The forms that it takes are many and disheartening, but by way of illustration, let me offer a few cases in point…

Case in Point 1

In the 1980s, the only way to talk to an immigration official was to get up very early in the morning and wait in a very long line. All applicants were handled by a single center on Rue d’Aubervilliers, where you could literally wait all day without getting to the front of the line. With this kind of system, before queuing up, you want to be sure that you’re in the right line.

In the 1990s, some changes were made, and immigration was handled by offices set up in four or five police stations all over town, each covering certain districts. So when I went to renew my resident card in 1998, I went back to the precinct house where I had renewed it before, but, knowing that the district assignments changed every year, I wanted to make sure that I was still in the right place.

There was a long line of applicants filling the sidewalk all the way around the block, and a policeman standing at the door to control entry. I went up and asked him if this was the right immigration office for the ninth arrondissement, my district.

It wasn’t (I found out later), but instead of just saying that, he started yelling at me: “You have to wait in line just like everybody else! You can’t just walk up here and butt in line! Get to the back of the line now! You’re no different…” etc., etc.

Explaining that I was trying to ask a question, not jump the queue, proved futile. Then I noticed that on the door, less than 10 centimeters from his head, was a sign saying, “For renewals, do not wait in line. Call for an appointment…,” with a phone number on it.

In other words, the bouncer in blue was ordering me to wait in line in order to find out if I was waiting in the right line, knowing full well that I was not. So I wrote down the number on the poster and walked away, daydreaming of that policeman’s silhouette in chalk lines.

Which brings me to…

Case in Point 2

There’s something about the job that turns some immigration officials (I would estimate about 20 percent) into imperious sadists. Many of the ones I dealt with took visible pleasure in demanding papers that were not on the official list of required documents. I learned to arm myself for every interview with photocopies of bank statements, tax returns, phone bills and bowling-alley shoe-check tickets just in case.

On one memorable occasion, I watched as a middle-aged Polish woman burst into tears of frustration when she didn’t have one of the requested documents, while the young woman behind the desk (no kidding) blew cigarette smoke in her face. Then again, maybe that was standard procedure to assess whether applicants could cope with life in France.

Case in Point 3

But most humiliating of all was the health check. All foreigners have to pass a medical exam to make sure they’re not bringing deadly contagion into the country: tuberculosis, cholera, etc. Emphysema’s okay, though.

So one frosty winter morning, I was summoned to a clinic in southern Paris for my “sanitary inspection of foreign nationals,” as they so poetically put it. There I was corralled into a locker room with about 50 other men and told to strip down to shorts and socks.

We were then divided into groups of six and herded through the stations of the “inspection,” an assembly-line-like process whose pared-down efficiency would have made Henry Ford gasp. Although maybe not in admiration.

Among other verifications, it included a chest X-ray, a blood pressure reading, a urine sample and, most efficient of all, a combination height, weight and vision check. For that one, I was ordered to stand on one of those old-fashioned scales with the built-in vertical yardstick.

One orderly wrote down my height and weight while another one at the other end of the room pointed with a ruler at the beginning of a line on an eye chart and ordered me to read it. I started rattling off the letters and he barked, “No! Just one!”

That was the test: one single letter. If you got it right, you were in. To this day I remember that mine was “H.” As in hale, hearty and humiliated.

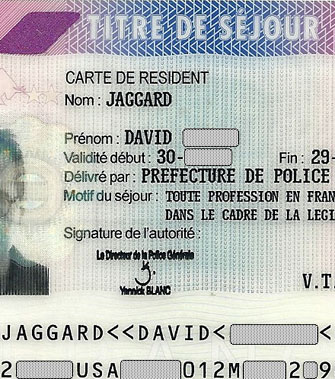

The health check was a one-time thing, but the waiting in line and second-hand smoke were an annual obstacle course for me for five years, after which I finally became eligible for permanent residency. In France, that means a 10-year card: it’s renewable indefinitely and allows you to hold a salaried job.

I was in a buoyant mood when I left the police station that day, armed with a receipt to be exchanged three weeks later for a permanent titre de séjour and thinking, “At last, the humiliation is over!”

So I thought…

Case in Point 4

One of the many things one has to submit to the immigration authorities is, of course, a photo. Or rather photos. Every time I renewed my card, I was asked for a different number: five, then three, then two and then four. I think on that first occasion the inspector just wanted one for his wallet.

In any case, for my 10-year card, I was asked to come back with four photos, three for my file and one to be laminated onto the card itself. So I went to one of those “four portrait” photo booths in the Métro, slipped my coins into the slot and sat there staring into the screen, trying to look French.

I had had extensive photo-booth experience by then and knew that there are two different types. Both give you four photos, but one takes four flash shots about 10 seconds apart, whereas the other has two cameras and flashes only twice to get the four portraits. This is explained in the instructions.

Which I hadn’t read. And so, after flash number one and flash number two, I began wondering: was this a four-shot booth, in which case I should steel myself for the third flash, or a two-shot booth, in which case I was sitting there for no reason like a not-especially-bright cargo cultist at an airstrip?

Just as I was raising my gaze, but not my head, to try to read the instructions posted above the camera screen, the third flash came.

So I ended up with three respectable-looking head shots and one kind of gargoylish one, but since I was out of both time and change, I decided not to start over.

Well, smart readers, you know what happened: I turned in the photos, and when I went to pick up my card three weeks later, my first official ID as a permanent resident of France was graced with a portrait of me in which my bulging eyes were rolled back in my head and my lips were puckered like I had just swallowed a raw snail that was squirming its way back up.

I regret to report that, even after turning my apartment upside down, I could not find my old card, so I can’t post that ignominious image here. But try to picture it.

And then consider this: since it’s mostly customs officials and border guards who examine that kind of ID, the idea is to look like a nice, cooperative law abider and not a terrorist or drug smuggler. But for a full decade my carte bore a photo in which I looked like I was already undergoing a body-packer exam as it was being taken.

Once again, I was so lucky! That they didn’t kick me out of the country.

© 2012 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.