The Fondation Louis Vuitton is presenting another blockbuster exhibition of a major Russian art collection, “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art,” following up on 2016-17’s showing of the amazing Shchukin Collection.

The Morozov Collection, full of masterpieces by great artists of the day, was put together by brothers Mikhail and Ivan Morozov in the late 19th and early 20th century with the help of leading art dealers in Paris and Russia. This show brings together some 200 predominantly French works.

The Morozovs collected many of the same French artists as Shchukin (they both owned versions of Matisse’s “The Dance,” for example, and plenty of works by Gauguin), but there are many differences between the collections. Among the many stunners in this show are beautiful works by Cézanne, Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Derain (in his Fauvist period) and even some especially fine paintings by Renoir, an artist I am not fond of when he gets too sugary.

The greatest pleasure of the exhibition for me was the discovery of Russian artists whose work I had never seen before. The first room features portraits of the Morozov family and friends by some of the leading Russian artists of the Day: Ilya Repin, Mikhaïl Vrubel, Valentin Serov, Konstantin Korovin, and Aleksandr Golovin.

The one who really stood out for me was Serov, whose lively portraits seem to truly capture the personality of his subjects, most notably in his 1901 portrait of Mikhail’s little son Mika. Children are notoriously difficult to paint, but Serov has managed to catch the boy almost ready to jump out of his chair in pursuit of whatever his eyes are fixed on. Serov also painted the 1910 portrait of Ivan Morozov sitting in front of a Matisse still life he owns that is being used to promote the exhibition.

Among the other Russian artists, I was struck by Ilia Machkov, especially the enigmatic “Self-Portrait and Portrait of Pyotr Konchalovsky” (1910), in which the two painters (supposedly referring to fellow Cubists and boxing enthusiasts Picasso and George Braque) are depicted as mustachioed musclemen wearing only underpants and socks. They sit in front of a piano looking out at the viewer. One holds a violin, the other sheet music. At their feet are sets of dumbbells, and behind their heads are two still lifes of flowers in vases in oval frames. The sheet music on the piano bears the name of a Spanish matador known as Bombita II, and the books on the shelf above it include the Bible and works on Giotto and Cézanne. I love the clash of machismo and high culture in the painting, and the way it seems to be telling a story but keeps it mysterious. According to the Virtual Russian Museum, “Mashkov’s portrait was perceived as a manifesto of a new movement in art, intending to make viewers pause, look and think.” That it certainly does.

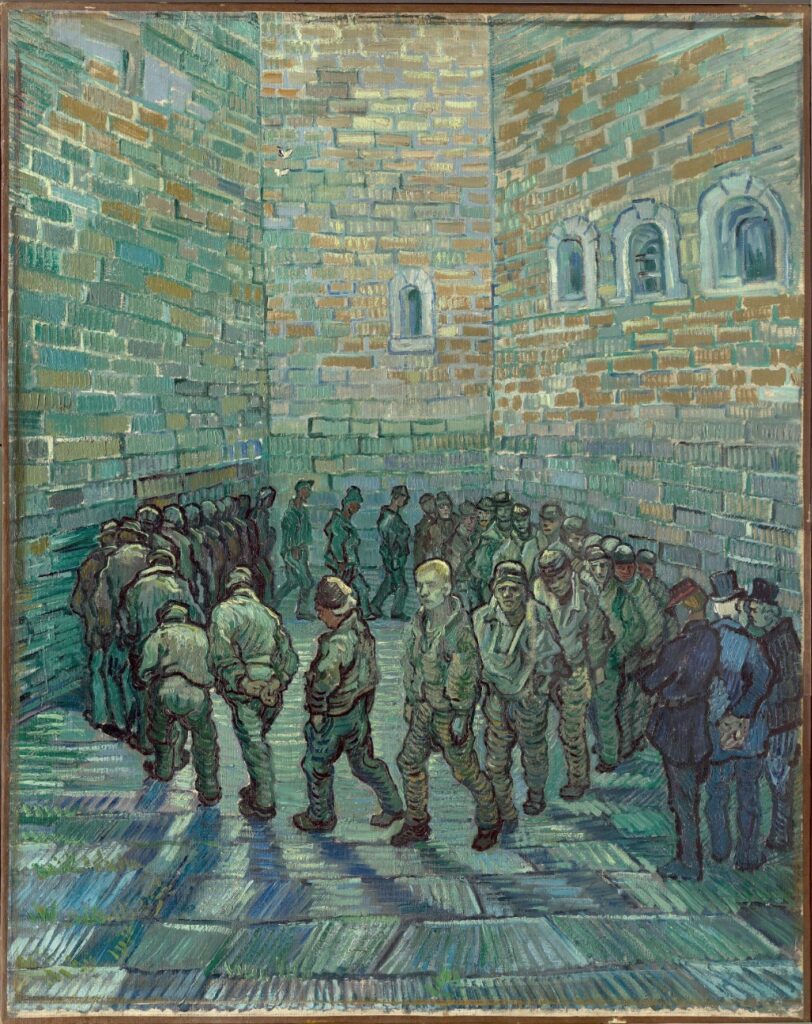

A couple of other anomalies in the show are a striking, very Nordic landscape (the Morozovs were particularly fond of landscapes), “Lake Ruovesi” (1896) by Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela, and a grim painting by van Gogh, “The Prison Courtyard” (1890), made when he was in the asylum in Saint-Rémy, France. Based on a drawing by Gustave Doré, it shows prisoners surrounded by tall brick walls walking in a circle (shades of Oscar Wilde), watched over by three guards. The confined painter’s normally vibrant palette has been replaced by drab grays, blues and greens, clearly expressing his state of mind, especially since the prisoner depicted in the center of the painting might be a self-portrait.

There is another unusual van Gogh painting in the show: the wonderful “Seascape at Saintes-Maries” (1888, pictured at the top of this page), which focuses attention on the wind-whipped waves and relegates the fleet of sailboats to the background.

While I didn’t find this exhibition quite as exciting as the Shchukin Collection, it is still well worth a visit for the many gems of French and Russian art on show.

Favorite

As I have been very ill for some time, preventing me from my once-annual month in Paris, I am now too tired at the end of a long day to give the above my complete attention. However, I would like to add that as a child growing up in the noted Somerset Hills of NJ USA, ca. 1945+ I attended for 13 years a “country day” (private) school in the company from Kindergarten of a child, Peter Morosov, whose father once a month took the club car to NYC on which my father travelled to his office. It was his understanding (or guess) that the somewhat standoff-ish Sergé Morosov was going to his bank in NYC to redeem deposits of invested monies by which to pay his family’s expenses. When we children played together at the Morosov home, an old NJ farmhouse of the 19th Century, seeming to me now as vaguely Russianified, the young US Mrs Morosov was very protective of her Russian husband and his need for quiet (as if he had been through a great strain). The Morosov’s did not socialize very much with other school parents, some of whom were European aristocrats and likely sensitive to the auslander in our midst. Years later, glancing through a survey book, as an art student, of French 19th C paintings, I saw one attributed to the collection, historically, of a great American family of wealth and public service, of which I am well acquainted with a member, our former Congressman. Thus curious, I looked to the footnote and saw the earlier owners as the Morosov family, noted Moscow retailers as stated. Even later, getting in touch with the son, Peter, still living somewhere nearby I found him not at all forthcoming — as many of our (few) former schoolmates and dropped, then, my researches.