Speaking of women-only exhibitions (see last week’s review of “Women in Abstraction”), I recommend a visit to the show “The Power of My Hands” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, which presents the work of 16 African women artists from different countries on the continent, some of whom live abroad.

While not all of these artists, as disparate as they are, take a direct political or feminist stance in their work, they all base their art on their own experiences, illustrating a feminist rallying cry of the 1960s and ’70s: “the personal is political,” a call to move the “intimate” issues of women’s life – e.g., sex, motherhood, childcare — into the public realm in search of political solutions to women’s issues.

Mother-daughter relationships loom large in many of these works. One of the most moving is South African artist Lebohang Kganye’s series “Ke Lefa Laka” (“Her-Story”). She made the series after her mother’s death in 2012, taking photos from her mother’s life – showing her reading at a table, posing in a bikini, dancing with another woman, participating in a march, etc. – and photographically inserted herself into each image as a ghostly presence dressed in similar clothes while imitating her mother’s pose and expression.

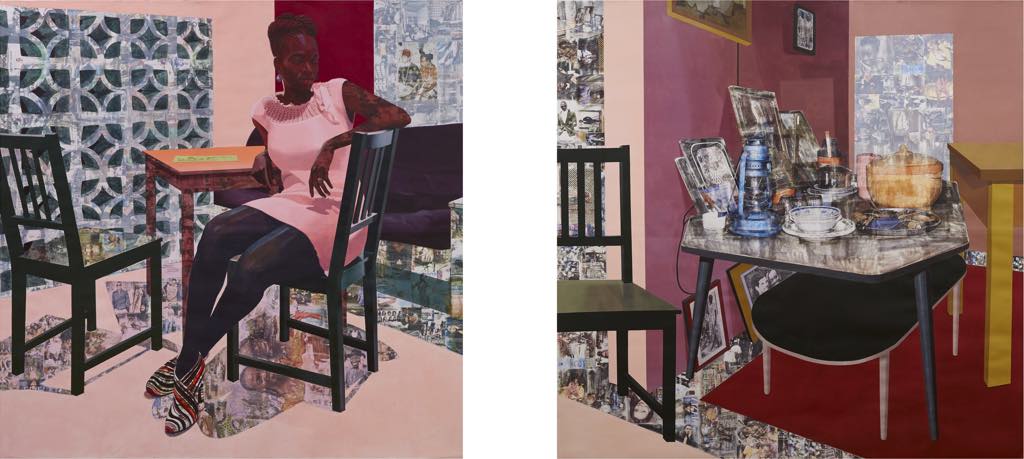

Los Angeles-based Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby also looks back to her family origins in handsome works combining drawing, painting, collage and photographic transfers. In “Predecessors” (2013; pictured above), the piece on the left shows her in her American apartment, while the one on the right depicts the living room in her grandmother’s home in a village in Nigeria, tracing a thread between their lives.

Thread makes an actual appearance in some of these works, notably the series “O Fardo” (2020) by the Angolan Ana Silva, who embroiders delicate images of people on the plastic bags in which secondhand clothing is transported to Africa. According to the curators, this is a comment on “corrupt social systems and the overconsumption associated with the fashion industry.” Be that as it may, the resulting images and colors are rather beautiful, suspended in the air like laundry and lit from behind.

Particularly striking is the work of Mozambican artist Reinata Sadimba (pictured at the top of this page), who makes ceramic and graphite sculptures that reference traditional pieces while defying the Makondé ethnic group’s ban on figurative image-making by women and dealing with such taboo subjects as naked women and pregnancy. There is something wonderfully appealing yet slightly creepy about these tattooed figures, with their cunning, fetus-like faces.

Children also feature in the work of Portia Zvavahera, who painted “Kubuda Mudumbu Rinerima” (“Rebirth from the Dark Womb”) after having a nightmare in which her daughter died. In the painting, the artist returns her daughter to the protection of the womb.

This show is a breath of fresh air, with its works by artists who will be unknown to many visitors and who have concerns that may be different from those of Western women artists yet are familiar in their universality.