In The Powers of Sound and Song in Early Modern Paris, Nicholas Hammond invites the reader to hear as well as to visualize Paris in the 17th century. This is, in many ways, counterintuitive, as we usually experience a period of history through its artifacts. This is especially the case with Louis XIV, the 17th-century monarch who took particular care with his image. We can visit Versailles and view the many artworks and objets d’art from the time of the Sun King, attend a production of a Molière play or watch a film like Le Roi Danse (2000) or a TV show like Versailles (2015).

Even today, we tend to rely on sight over the other senses. Many recent studies have argued that, in an age of social-media saturation, some restaurants are sacrificing taste to making dishes look picture-perfect and that the presentation of food can impact our perception of the flavors.

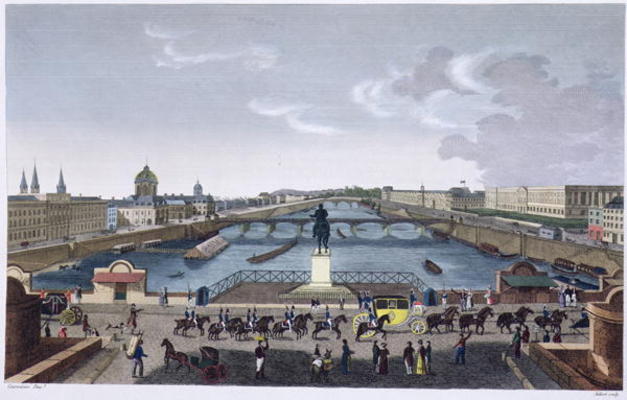

The Powers of Sound and Song gives us a different flavor of life in Paris at the time, particularly as it occurred on the Pont Neuf. Given that the bridge, which was finished in 1607, is so spacious and usually fairly sedate today, it is surprising to learn that it was once filled with so much hustle and bustle, “defined above all by noise and disorder,” according to Hammond. Sellers offering all kinds of merchandise could be found along the bridge, along with carriages, pedestrians, singers, musicians and diverse crowds of people, including thieves, prostitutes, and charlatans. It was the most popular spot in the capital for that most ancient of Parisian pastimes: people-watching.

In fact, as “the city’s first truly communal entertainment space,” the bridge was most likely responsible for shaping and cultivating this pursuit, as the book points out. Starting with the bridge, Hammond takes us on a journey involving some of the people whose worlds collided there. One of the many interesting and unexpected facts we learn is that a huge degree of social mixing took place on this span over the Seine.

It was also a place where marginalized individuals like the disabled could gain a living, acceptance and even a fan base. One of the regular characters on the bridge was Philipot le Savoyard, a blind songwriter and performer whose rich repertoire was published and who imitated court songs. He was also mentioned in the poet Nicolas Boileau’s work, in a demonstration of a two-way channel of influence that runs counter to the model we usually have of elite culture trickling down to the masses.

Hammond fleshes out what kind of man Philippot was through a closely argued interpretation of his lyrics, revealing a sensitive artist who tried to communicate to his listeners the experience of being blind without seeking to elicit sympathy. We discover an artist who “sees” blindness not as an impairment but rather as an integral part of who he is and what he has become: “I am the famous Savoyard / Who through the skill of my own art / Overcomes melancholy.”

The bridge was also the place where people went to be seen and where news about current events or the failings of the great and good was first talked about and disseminated – social media avant la lettre. The poems recited and songs sung about the famous and infamous were on occasion highly subversive in their criticism of authority, even if seemingly innocent on the surface. Historians have had a tendency to overlook or even dismiss low-brow culture and Hammond persuasively shows why they are not only missing the point but also are missing out.

Sound was a vehicle for expressing dissatisfaction and even dissent, and Hammond argues that popular songs offer rich material for deciphering what was going on in this world and, more importantly, what people were really thinking – and not just common folk: Madame de Sévigné, a well-connected aristocrat now famous for her witty correspondence, frequently evoked the melodies and ditties she heard on the Pont Neuf. To the point that, as Hammond notes, a song she mentions in 1671 is later referred to in one of her final letters in 1695.

If the Pont Neuf is one of the most significant places in this study, then 1661 is the crucial date. This is the year in which, following the death of his first minister and father-figure, Cardinal Mazarin, Louis XIV decided to assume personal rule and stop delegating affairs of state to a favorite. In doing so, Louis (and his ruthlessly ambitious acolyte Jean-Baptiste Colbert) had to eliminate Mazarin’s expected successor, the highly successful and flamboyant finance minister, Nicolas Fouquet, who was tried on trumped-up charges of embezzlement of state funds in one of the greatest injustices in French history until the Dreyfus Affair two and half centuries later.

Songs circulating on the Pont Neuf show how initial negative sentiments toward Fouquet were displaced by an increasing sense of the abuse of justice that unfolded during the lengthy three-year legal proceedings. These critical songs reached the ears of the court – and the monarch.

Initially, Fouquet’s family was dismayed by the choice of judges running this show trial, among them Olivier Lefèvre d’Ormesson. Hammond demonstrates how d’Ormesson, rather than being the yes-man they expected him to be, ended up following his conscience and arguing eloquently against executing the prisoner, thus cheating Louis XIV of the death sentence he hoped would be given to Fouquet.

Madame de Sévigné’s letters gave a vivid depiction of the sound world of the courtroom through her reporting of the spoken words of her friends Fouquet and d’Ormesson, which succeeded in changing the course of the trial. The king punished d’Ormesson by snubbing him thereafter, but popular songs lauded his courage. Michel Foucault famously observed that “where there is power, there is resistance,” and the Pont Neuf played its part in resisting the excesses of government.

The last part of the book reads like a detective story, taking as its cue a four-line song stating that an unfortunate man called Chausson was going to be burnt at the stake for the same offense for which another man, Guitaut, was about to receive the blue sash of the cordon bleu, the highest order of chivalry in the land. Having found manuscript evidence to get to the bottom of the mystery, Hammond reveals that both men were gay, but while the lower-born Chausson was burned at the stake for practicing same-sex love, Guitaut, the favorite of the Prince de Condé, one of the most powerful men of the kingdom, was honored. It is revealing that the song does not condemn same-sex love but rather institutional hypocrisy, expressing a sense of outrage that resonates in today’s society. Plus ça change…

Hammond brings life to the past and offers a fascinating and thought-provoking book, packed with anecdotes and colorful characters, that is of interest both to general readers and scholars. Along the way, we learn about key events during the 17th century and delve into the lives of a network of interconnected figures. Above all, we witness people not unlike ourselves dealing with much the same issues and challenges as our own.

The historian Jacques Le Goff ended his seminal 1964 survey of the Middle Ages, La Civilisation de l’Occident Médiéval (Medieval Civilization, 400-1500), by considering how, in looking at castles, wars and royalty, we forget all of those ordinary folk whose humble houses, like their existence, have disappeared forever. The Powers of Sound and Song in Early Modern Paris redresses this imbalance and gives us a panoramic cross-section of Parisians. Hammond concludes this page-turner by highlighting how the songs and sounds of early modern Paris “give voice to people who would otherwise have remained silent.” He is to be thanked for making them heard today.