I was going to start this review of Elaine Sciolino’s new book, The Seine: The River That Made Paris, with a disclaimer, as I was involved with it in a very small way, but, as Sciolino does not acknowledge my help, such a disclaimer is probably unnecessary. The author summoned me to tea a couple of years ago to question me on my knowledge of the song culture that flourished on the Pont Neuf in the 17th and 18th centuries. I gladly gave her two hours of my time, followed up by a number of e-mails from one of her researchers. In the end, only one paragraph (on p. 181, if you’re interested) is incontrovertibly based on my work. Snubs aside, I hope nonetheless to give a fair-minded appraisal of this richly researched and entertaining book.

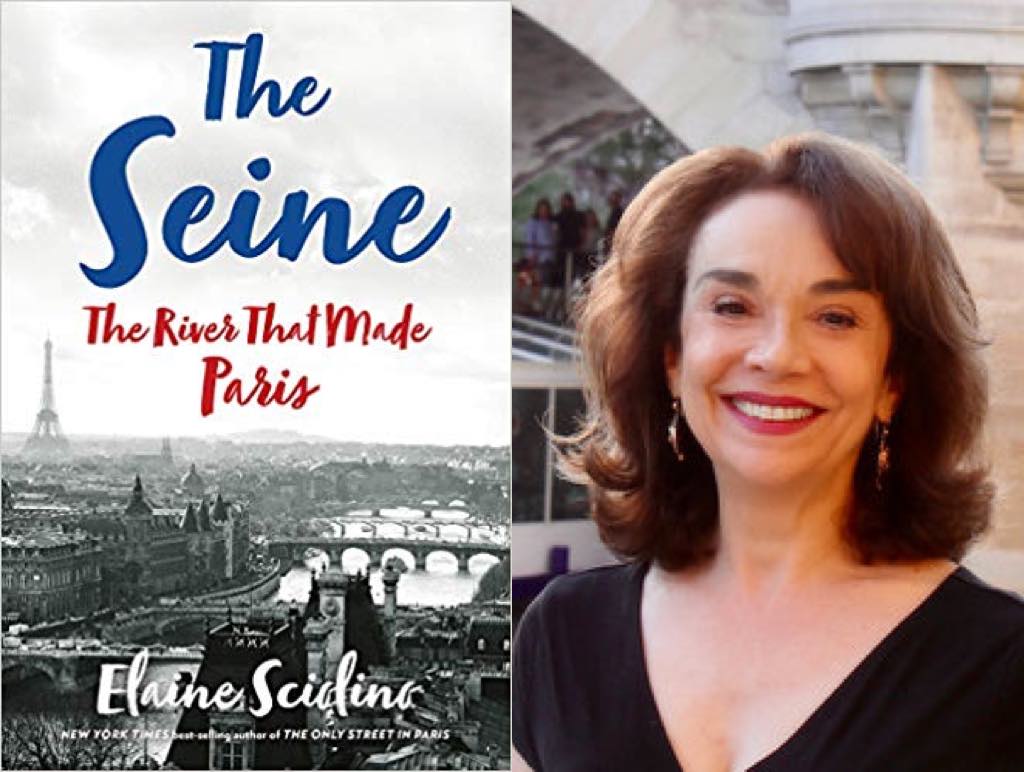

A former Paris bureau chief for The New York Times, Sciolino has written four previous books on French themes, most recently her beguiling evocation of the Rue des Martyrs, The Only Street in Paris. Her new book has a much more ambitious scope. As it tries to capture the many facets of the River Seine, it moves from the river’s source in Burgundy to Normandy, where it joins the sea, along the way lingering for much of the book in Paris, as one would reasonably expect.

Sciolino succeeds above all in communicating a wealth of historical and factual detail about the Seine in an engaging and distinctive way, often delving into unexpected aspects of the river. She is ever alert to the place played by the Seine in art (above all, the paintings of the Impressionists), literature and the cinema. And her championing of Sequana, the Gallo-Roman goddess of the Seine, as an appropriate figure to head the 2016 initiative to reinvent the Seine, runs as a glorious leitmotif throughout the book. I will refrain from telling the reader whether her bid succeeded or not.

The force of Sciolino’s personality lies at the heart of all her explorations in this book and will no doubt enchant some readers as much as it will irritate others. As early as the second paragraph of the book, we learn that she was abandoned by a first husband in Chicago, and almost every encounter is recounted as a major coup on her part. Her enthusiasm and drive are infectious, though, even if the endless succession of transcribed interviews/conversations with various luminaries and boat-dwellers can at times be monotonous and could have been pruned. Similarly, as understandable as it might be for the sake of adding color, very little is gained by reading about the banal outfits that the author wears to various meetings, such as when she visits a man on a boat at the time of the Paris floods: “I donned an anorak, jeans, a small backpack, and rubber-bottomed work shoes.”

Given the forensic detail with which she studies various sculptures, ancient boats and artifacts related to the Seine, it comes as a surprise that the depiction of the Seine (alongside the other major rivers of France) in the Louvois Fountain (right next to the old site of the Bibliothèque Nationale on Rue Richelieu) escaped her attention, but the overall range of her inquiries is hugely impressive.

The book’s Afterword, written soon after the fire that almost destroyed Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, is particularly touching as Sciolino explains how the water pumped from the Seine was crucial in saving the edifice.

This delightful, if flawed, book certainly taught me a lot about a river I thought I knew well. It should be recommended reading both for those who love Paris and for those intending to visit France anytime soon.

Buy The Seine: The River That Made Paris.

Favorite

Good review! I read and enjoyed this book, but as I have read other books on the Seine, I thought it slightly flawed myself. I still recommend it, as it contains a wealth of information on so much, and will keep you interested from cover to cover. I particularly found the chapter on the bouquinistes enjoyable and informative. I guess I never thought much about the history and administration of these stalls, so learning about the rules and regulations was eye-opening.

All in all, there is something new for most readers contained in the pages of this narrative, and although it may have benefited from editing out some of the purely personal asides, it is certainly worth the read.