Egyption Art Lives On as

Civilization Declines

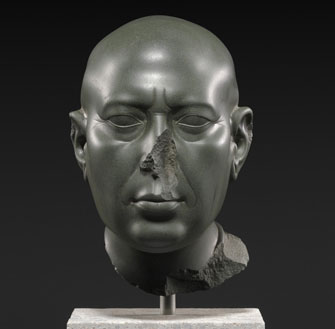

The Berlin ”Green Head,” from the Ptolemaic Period (c. 350 B.C.E.) © SMB Agyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung. Photo: Sandra Steiß

The new exhibition at Paris’s Musée Jacquemart-André, “Le Crépuscule des Pharaons: Chefs-d’œuvre des Dernières Dynasties Egyptiennes” (“The Twilight of the Pharoahs: Masterpieces from the Last Egyptian Dynasties”) sets out to rehabilitate the bad rep of ancient Egypt’s final millennium, during which successive decades of invasions – from Libya, Nubia, Persia and Greece, before the final fall to Rome in 30 B.C.E. – interspersed with periods of local rule, disrupted not only political life but also artistic traditions, with some outside rulers imposing their own style diktats. Overall, however, respect for Egyptian culture reigned, and the arts of Eygpt continued to flourish, especially during the Saite Period (672-525 B.C.E.), with some stylistic variations.

The show takes us through those variations with over one hundred pieces from some of the world’s finest collections of Egyptian art, including the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin, the British Museum, the Louvre, the Metropolitan in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

A collection of statues illustrates the various ways people were depicted in different periods: standing, kneeling, with more or less realistic treatment of the body and its stance and musculature. One standout in this section of the show is a block statue of Hor from the Libyan period, in which the body of the god, seated with his knees drawn up to his chest and his arms folded over them, forms a cube with incised drawings on its front of the falcon-headed god Montou and Osiris of Abydos facing each other.

A roomful of busts is fascinating for the varying degrees of naturalism in the depiction of the face, ranging from idealized features to sad expressions, wrinkles, bags under the eyes, big noses, and even beaming smiles. The upper part of a statue of a man from the Ptolemaic Period (332-330 B.C.E.) shows a departure from the familiar frontal pose. The torso is slightly twisted, and the rather feminine-looking man has a Mona Lisa smile, as do many of the other works in this room. The star here is the Berliner “Green Head” (c. 350 B.C.E.), pictured above, of a priest who looks so real – even though most of his nose is missing – that you think he might open his mouth and speak. The bumps on his shaved head are convincing modeled, although his crow’s feet and the deeply incised furrows between his brows – which, along with the bags under his eyes, indicate that he is not a young man – are given a rather cursory treatment.

Then we come to the realm of the dead, the Egyptian specialty. A number of exceptional pieces are presented here, including a colorful, beautifully preserved painted papyrus scroll covered with scenes from The Book of the Dead. One room contains the most important pieces from the tomb of a provincial priest named Ankhemmaat, dating from the fourth century B.C.E., among them the funerary mask, mummiform coffin, statuettes of funerary servants accompanying him to the afterlife (where, since everyone is required to toil in the fields, a servant is taken along to replace the deceased person every day of the year so he or she could relax), a painted wooden chest to hold his viscera (instead of the canopic jar, which was commonly used for this purpose before the Ptolemaic Period).

The exhibition continues with nude statues of women, generally idealized and sometimes fatter and sometimes thinner, followed by a section of depictions of pharaohs, which mostly follow Egyptian traditions, with the notable exception of the depictions of Persian ruler Darius, made in Persian style by Egyptian artists. The show ends with statues of the gods and goddesses, many of them in the form of animals, among them a wonderful statue of Thoth as a baboon, and another of Bastet as a cat, known as the “Gayer-Anderson Cat” (664-525 B.C.E.).

At the opening of the exhibition, I overheard one of the curators scornfully saying that when antique dealers see an ugly Egyptian object, they automatically describe it as “Ptolemaic.” Perhaps they will change their tune after seeing this show, which successfully makes the case that the thousand-year “decline” of the pharaonic era did not spell the end of Egyptian artistic brilliance.

Musée Jacquemart-André: 158, boulevard Haussmann, 75008 Paris. Métro: Saint-Augustin, Miromesnil or Saint-Philippe du Roule. RER: Charles de Gaulle-Étoile. Tel.: 01 45 62 11 59. Open daily, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. (until 9pm on Monday and Saturday). Admission: €11. Through July 23, 2012. www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com

Reader Ron Fox writes: “A fascinating show, as interesting for its objets d’art as for the history that it explains.”

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2012 Paris Update