Back in the late Sixties, the Velvet Underground would have seemed an unlikely subject for an exhibition like “The Velvet Underground: New York Extravaganza” at the Philharmonie de Paris. Though well-received by perceptive reviewers of the time and played by a few hip disc jockeys on public and underground stations, their albums sold only modestly, and the band got relatively little attention in the press once it separated from its early mentor, Andy Warhol, who made it part of his multimedia Exploding Plastic Inevitable events (Warhol’s New York answer to Ken Kesey’s West Coast Trips Festival, which featured the Grateful Dead).

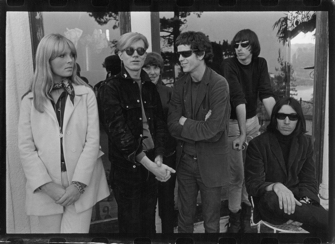

The band only began to take on status as a legend in the Seventies, when it was already defunct, and Lou Reed and John Cale – as well as Nico, the German singer who accompanied them on their first record (the “banana album”) and during their Warhol phase – had embarked on solo careers. The exhibition, designed in a way that captures Warhol’s multimedia style, charts the history of both the band and the New York counterculture from which it emerged in the mid-1960s.

The show gets off to a rousing start with Allen Ginsberg’s playful 1956 poem “America” and a multimedia panel of popular TV shows from the mid-Sixties like “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” and the first James Bond film, Dr. No. Ginsberg appears again in a filmed interview speaking in French about psychedelics.

A collection of photographs by the great Fred W. McDarrah includes two from 1959 of Ted Joans, in later years a beloved fixture on Paris’s literary scene. Back in the late Fifties and into the Sixties, Joans was a Rent-a-Beatnik, as was the poet and satirist Tuli Kupberberg, who formed the Fugs with another poet and writer, Ed Sanders, in 1964. Edward English’s 1966 film of the Fugs playing such immortal gems as Tuli’s “Kill for Peace” (sadly still relevant), “Group Grope” “Slum Goddess” and “Doing All Right” is one of the exhibition’s many highlights.

The exhibition also features Barbara Rubin, who introduced Warhol to the Velvet Underground. Her Christmas on Earth, the most sexually explicit non-porn film ever made and an experiment in liberation and joy, was made when she was barely 20 years old. A star of New York’s underground film world, Rubin also appears as a nun in the film for the Velvet Underground’s song “Venus in Furs.”

This section also celebrates Angus MacLise, a poet, bookseller, musician and shaman who was the Velvets’ first drummer, before the excellent Maureen (Moe) Tucker. MacLise, with John Cale, was influential in developing the early Velvets’ drone sound, while the “happenings” he promoted were forebears of Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

Another film describes the very different backgrounds of the Velvets’ founders, Reed and Cale. Reed was a troubled middle-class Jewish boy, born in Brooklyn and raised on Long Island, who was given electroshock treatments as a teenager. Later, while at Syracuse University, he met Sterling Morrison, who became the Velvets’ guitarist.

Cale was a scholarship boy from Wales who traveled to New York to work with John Cage and La Monte Young. His electric violin and viola playing and his immersion in Young’s techniques marked the Velvet Underground’s first two albums. Cale’s musical dissonance and knowledge (along with MacLise’s) combined with Reed’s basics (mixed with folk strains and his beloved doo-wop) to create an entirely new sound that proved perfect for Reed’s poetic urban storytelling. The film mentions in passing that the band was briefly called The Warlocks, a title shared, unwittingly, by the future Grateful Dead on the other coast at about the same time.

For all of Cale’s avant-garde contributions, they were essentially frills that disappeared when he left the Velvets in 1968. Reed wrote the lyrics, though he sometimes collaborated with his band mates on the music – Cale and Nico both emerged as brilliant songwriters, matching Reed, when they went solo.

Véronique Jacquinet’s too-short film tells the story of Nico, who figured in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita before Bob Dylan and his then-manager talked her into going to New York. Though she might have been more at home in Dylan’s orbit than Warhol’s, she soon found herself at the Factory in New York. Warhol’s screen test of her, shown here (along with those of the Velvets), is a gem that captures her astonishing beauty. Cheetah magazine called her “the poet’s lady,” and she became for a time the muse for Leonard Cohen and Tim Hardin. On her own, she wrote beautiful mournful, poetic songs, self-accompanied on a harmonium, that seemed closer to the sounds of the Middle Ages than the late 20th century and were appreciated by the few. “Famous but not popular,” as a Japanese promoter said in the Eighties.

Reed only allowed Nico to sing on a few of the Velvets’ songs (she wanted to do all of them). This despite the likelihood that the band only got a record contract because Tom Wilson (who really produced the first album, though Warhol took the official credit for commercial reasons) liked Nico and thought she could become a great star. Warhol and Warhol’s manager, Paul Morrissey (who also managed the Velvets at the time), had imposed her on the band, and Reed did fall in love with her for a while. Nico left the group in mid-1967, but Reed, Sterling Morrison, Cale and a teen-aged Jackson Browne all played guitar on Nico’s beautiful first album, Chelsea Girl.

The section on the Exploding Plastic Inevitable includes films celebrating everyone from Warhol’s right-hand man, the poet Gerard Malanga, who choreographed the Exploding Plastic Inevitable and appeared on stage, kinkily wielding a whip in time to the music, to Warhol himself; Danny Williams, the brilliant editor who disappeared without a trace in 1966; and the ill-fated Edie Sedgwick.

The Factory’s strong element of willful decadence was carried over into the Exploding Plastic Inevitable and many of the Velvets’ lyrics. This helps explains the hostility the show met when it played Los Angeles’s Trip and San Francisco’s Fillmore. Ralph J.

Gleason, a distinguished San Francisco jazz critic who embraced rock, panned the Velvets as “lame” and not to be compared to the Airplane or the Dead, adding that the light show reeked of “café society camp” and “Greenwich Village sickness,” and was trying to cash in on the light shows that were part of Ken Kesey’s Trips Festival and carried on at the Fillmore and Avalon.

The re-creation of the scene around Warhol is so fascinating that the rest of the story, after the Velvets separated from Warhol (and soon after that Nico and then Cale) seems almost an epilogue (at least in the exhibition), even though the Velvets’ members made some of their best music afterward. Still, this wonderful exhibition does a great job of capturing what it was like to be there then.

Favorite