Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Paris Update on June 8, 2014.

As I write this, the 2014 FIFA World Cup is about to begin in Brazil. This quadrennial tournament always brings back a fond childhood memory for me. Not of watching my country’s team win — I grew up in the United States before the “beautiful game” was part of the sports scene — but of an incident that remains to this day one of the funniest things I have ever seen in my life: American teenage boys in 1970 trying to play soccer.

I was one of them — this happened during my junior year in a small Midwestern public high school. In those days no one in the United States paid attention to the sport that the rest of the world calls football. (Even the French use the English term, although the Académie Française dictionary helpfully explains that it means “balle au pied.”)

Here in France le foot (the French often drop the “ball”) (parentheses for rent: your pun here!) is the national pastime, if not the national obsession, but in the States back then nobody knew anything about it. There were no children’s leagues, no well-known professional teams and no games on TV. My entire understanding of soccer could be summed up in three points:

1) There’s a ball.

2) People kick it around.

3) For some reason.

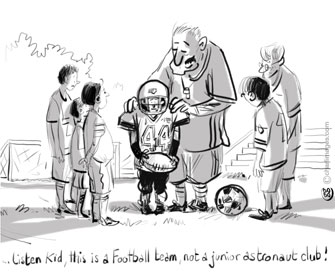

That was it. So when the boys’ P.E. teacher announced one day that we were going to play soccer, neither I nor any of my classmates had any inkling of the actual rules. The first thing the coach told us was, “You can’t touch the ball with your hands.”

For a bunch of baby boomers, whose team sports awareness was essentially limited to baseball, basketball and what our little chunk of the world calls football, this was a source of great consternation. There arose a chorus of disbelief — “You what?” “With your what?” “REALLY?” — until the teacher added, “Except for the goalie.”

This triggered a new outburst as half the class tried to get “dibs” on a position they could at least dimly relate to: “I’m gonna be goalie!” “No, I’m the goalie!” “I said it first!” “Yeah, but I reached puberty first,” etc.

Which was compounded by the next announcement: “But the goalie can’t leave the box around the goal.” Since everyone wanted to be at the center of the action as much as possible (more on this later), that news sparked yet another vociferous dispute: “Okay, you can be goalie!” “No, you’re the goalie!” “You said it first!” “Yeah, but you wear white socks,” and so on.

We then did a couple of drills that were supposed to teach us how to dribble the ball between our feet. They didn’t.

This was the first time any of us had ever tried to use those white-socked appendages for anything more intricate than passing notes along the floor in class, and, as Napoleon said upon returning from Moscow, we sucked. None of us ever managed more than three or four steps without either losing the ball or tripping over it. And then losing it.

After about 10 minutes, the coach, apparently giving up on teaching us more advanced techniques like heading the ball and pretending to be injured, decided to let us play a game. Or I should say “play” a “game.” We formed two teams, divided, in compliance with Article I of the United States Constitution, into “shirts” and “skins,” and took to the field.

Then came the funny part. It’s important to remember here: we were teenage boys — in other words, ambulant testosterone geysers. This biological fact affected our behavior in a number of ways that would not have surprised Jane Goodall, and in gym class that day it meant that all the players on both sides felt a deep, visceral, primal need to be the one kicking the ball. At all times.

So when the teacher blew the whistle to start the match, all the boys who hadn’t been forcibly relegated to goalie duty immediately rushed to the ball and started kicking as though their future sex lives depended on it. For the rest of the “match,” the entire class, with the exception of the goalkeepers (plus me and a friend of mine after we realized how comical the whole thing was), spent the entire time crowded in a tight circle around the ball, all of them kicking constantly and more or less blindly as fast as they could.

The chances of any given kick not being instantly countered by two or three concurrent kicks from elsewhere in the circle were exceedingly slim, but eventually the ball would accidentally ricochet up and out of the pack in a totally random direction, and everyone would sprint, in close formation, over to wherever it landed and resume the kickfest.

It went on like this for the rest of the class period, with that poor mistreated blob of leather caroming around in a jungle of flailing legs like a golfball in a blender, never coming anywhere near either goal.

During all this time, it never occurred to any of the would-be Pelés that their soccer style, i.e., treating the ball like a pinata filled with winning lottery tickets, was stupid and futile — the equivalent of sending every member of a baseball team up to bat at the same time, or playing dectuples tennis.

The only ones to learn anything from the experience were the goalies, who were taught one of life’s great lessons: good (or any other kind of) things don’t always come to those who wait.

The 1970 World Cup took place later that year in Mexico, where the Brazilian team, with the real Pelé opening the score, whipped Italy four to one in the final. The United States wasn’t even in the tournament and didn’t qualify for any subsequent World Cups until 1990.

I suspect that my phys ed class was responsible for this. My theory is that the coaches of the men’s national team happened to be passing through my hometown that day, saw us in the school practice field and became so despondent they all quit. And got jobs selling leisure suits and home disco systems just so they could have some kind of hope for the future.

This is the first installment of a two-part article. Part Two is here.

© 2014 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.