When the news broke, it swept across Paris like a shockwave. All over town, Parisians dropped their jaws, espresso spoons and social benefit checks in disbelief — how could the municipal government even think of such a radical, far-reaching piece of legislation?

I refer, of course, to the recent City Council decision to allow bicycles to run red lights. Sort of. To be precise, the new measure states that cyclists are now authorized to turn right or, if there is no street to the right, proceed straight ahead on red, under the condition that they “exercise caution” and — the official announcement stresses this point emphatically — yield to pedestrians. Readers who have had any dealings at all with Parisian bicyclists are already laughing.

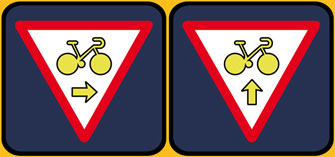

The City Hall communiqué goes on to specify that this rare, exceptional privilege is only allowed at certain intersections, marked by newly created signs showing the outline of a bike and a yellow directional arrow:

As anyone who has ever witnessed Paris traffic for more than 30 seconds knows, the introduction of these two road signs represents the most heinous, pointless waste of paint, metal and manpower since the guillotine.

This is because the majority of Parisian cyclists already see their vehicles as a de facto exemption from the rules of civil society, like little mobile islands of diplomatic immunity. Which is why I sit on a bicycle to fill out my tax returns.

For a Parisian bike rider, stopping for a red light is like calling the snakebite hotline, restraining flatulence or, for that matter, filling out tax returns: no one does it unless they really have to.

Wondering what effect, if any, the new law was having on actual bicyclical behavior, I decided to do a little field research. As I learned from the above-mentioned-and-linked Web site, so far the signs have only been installed in two neighborhoods around Gare de l’Est, so thither I went.

Methodology

By deploying the time-tested scientific technique, pioneered by Moses and honed by urban anthropologists over the centuries, of wandering around aimlessly in the vague general area of what I thought I was looking for, I found three of the right-turn signs.

After picking one on an especially busy street along the Canal Saint Martin, I set up an observation post consisting of two feet held in place by gravity on the sidewalk serving as the base for an organic life support system fueled by a 33-centiliter can of cola and integrating a dual-lens optical image recognition unit, and stood there monitoring traffic patterns until, again in compliance with strict scientific protocol, I got bored.

Which took about 11 minutes. During the first two, to my surprise, every biker who reached the intersection when the light was red stopped. Then, just as I was thinking, “There’s never a lawbreaker around when you need one,” the pedal-propelled miscreants began arriving in a steady stream, like a teamless, uniformless, disciplineless Tour de France.

For the next nine minutes, not one operator of an unmotorized two-wheeler made any pretense of even slowing down — they all sailed through the light, whether turning right, turning left or going straight ahead.

Conclusions

Having thus observed a significant sample, I can report with confidence and a low statistical margin of error that one-fifth of the cyclists in the test group stopped at the red light and simply waited it out, even if they were turning right, and the other four-fifths disregarded the light completely, as though all those poles flashing red and green on the side of the road

were leftover Christmas decorations.

In other words, the turn-on-red sign might as well have been tacked to the underside of the nearest sewer grate. The 20 percent of law-abiding cyclists seemed to be oblivious of their new prerogative and the other 80 percent seemed to be oblivious of everything, including the meaning of “traffic code,” the existence of other vehicles and the invention of brakes.

Our tax euros at work! But since the municipal government is already acting as though it’s in the employ of the powerful C’est Ironique lobby, it made me wonder: now that they’ve spelled out conditions under which citizens can ignore a law that most of them never dreamed of obeying in the first place, what other measures might be enacted to enshrine long-standing and widespread contempt for the rules?

I have some suggestions. Four, to be precise:

1) Certain conditions could be specified under which adultery would not be admissible as grounds for divorce. Specific seedy hotels where couples could, exercising caution, yield to their un-altared natural impulses would be marked with the same sign as for the bike turns, but with two horizontal stick figures instead of the bicycle and two yellow arrows instead of one, pointing in opposite directions.

2) For the benefit of Paris’s many hotheads who feel obliged to escalate all insignificant accidents and misunderstandings into assault and battery cases, arenas could be set up where they would be able to vent their aggression against adversaries of equal weight, fighting ability and emotional immaturity, pummeling each other within a roped-off space until one of them yields. To exercise caution, they could wear padded gloves that minimize the risk of injury. I’m surprised that no one has ever thought of this before.

3) Boarding passengers who charge the doors of crowded Métro trains before anyone has half a chance to get off could be sedated, airlifted to a dark detention center and force-fed tête de veau so that they would have at least one brain cell somewhere in their bodies. This has nothing to do with my analogy, nor is it at all humane or feasible, but I just like thinking about it.

4) Cautionless, non-yielding motorists who insist on exceeding the speed limit in town, thus endangering themselves and everyone within a radius of their much-extended stopping distance, could have a special zone set aside for them with less traffic and fewer intersections, where they could safely go as fast as 130 kph. Oh wait — we already have that. It’s called “the countryside.”

And maybe, just maybe, they could even be allotted a place somewhere with wide, well-tended roads upon which they would be allowed to drive as fast as they want, exercising no caution and yielding to no one, with no speed limit whatsoever. Oh wait — we already have that, too, and it’s already marked with signs. They say “Welcome to Germany.”

© 2013 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.