|

|

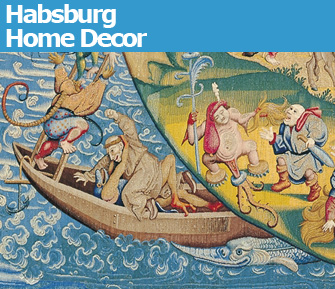

Detail of “The Haywain” (“The Temptation of Saint Anthony), after Hieronymus Bosch. © Patrimonio |

What a shame that the Galerie des Gobelins doesn’t allow visitors to borrow some of the tapestries on show in its latest exhibition: “Treasures of the Spanish …

|

|

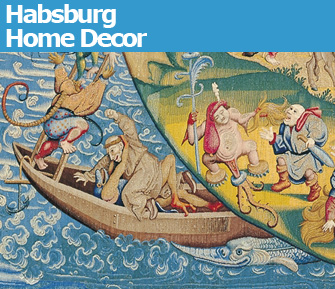

Detail of “The Haywain” (“The Temptation of Saint Anthony), after Hieronymus Bosch. © Patrimonio |

What a shame that the Galerie des Gobelins doesn’t allow visitors to borrow some of the tapestries on show in its latest exhibition: “Treasures of the Spanish Crown: A Golden Age of Flemish Tapestry,” since the only way to fully appreciate these beautiful, complex, storytelling wall hangings is to live with them the way their original owners did (one slight problem: few of us have castle-sized walls large enough to hang them) and study them carefully and at length. The more you look, the more previously unnoticed details emerge.

As I walked around the gallery’s spacious, airy galleries, filled with natural light from ceiling-high windows and blissfully uncrowded in spite of the treasures hanging on the walls, I wished I had an expert guide (or several; many areas of expertise would be required) who could explain the myriad biblical and mythological references woven into the 20 or so tapestries from the collection of the Spanish royal house during the late 15th century and the first half of the 16th. At that time, it ruled over the Netherlands through the Spanish branch of the Habsburg Empire, and the royals took advantage of the superior talents of Flemish artists and tapestry workshops, mostly in Brussels, to decorate their homes with the very best of these marvelous “mobile frescoes,” which not only helped keep them warm in their damp, chilly castles but also adorned the walls, entertained with visual stories, served an educational purpose and could be easily carried from castle to castle.

I longed for someone to explain what was going on in “Le Chevalier au Cygne” (1482), for example, which is supposed to recount the mythical origins of the House of Cleves, in which a lady-in-waiting seems to be offering an armful of puppies (or are they piglets?) to a lady in the bottom half, while in the top half two gentlemen are passing something from hand to hand.* In another piece, “The Descent from the Cross” (1507-20), one onlooker with crossed arms, visibly unmoved by the death of Christ, cranes his neck to look at an urn sitting on the ground. Is he a thief?

Each of the stunning works in this show is fascinating in a different way. “The Haywain” (or “The Temptation of Saint Anthony,” 1550-70), after Hieronymus Bosch, for example, must have caused nightmares in more than one inhabitant of the rooms it decorated with its unspeakably terrifying monsters infesting the waters around the central globe, where greedy humans fight over the contents of an overloaded hay wagon and risk falling into an ogre’s gaping maw.

An earlier work, the monumental “La Fortune” (1520-1525) made by Pieter van Aelst, teems and swirls with dozens of figures and moralizing events that require a thorough classical education to untangle. Luckily, the weavers have provided names to help us. The little boat carrying a woman and baby amidst the chaos of people drowning in a tsunami is labeled “Danaë,” who had been cast into the sea with her baby, Perseus (son of Zeus, who took the form of a shower of gold to impregnate her), by her father because of a prophecy that his grandson would kill him.

One complaint about this show: the curators seem more interested in which member of the Spanish royal family owned which tapestry and what series it belonged to – matters of great interest to art historians perhaps but not to amateurs – than in explaining the rich iconography we see in these works. English museums do a much better job of providing succinct, interesting and informative descriptions of works of art; while French museums have been doing better lately, some of them still have a long way to go.

We do, however, learn a little bit from this show about the evolution of tapestry-making and artistic tastes and styles during the time period covered: we see the introduction of perspective and how the figures became more clearly defined to enhance the educational role of the tapestries, as well as how they were used to illustrate the political might of the Habsburgs and commemorate battle victories. Those with religious subject matter were meant to inspire piety and, while they may no longer fulfill that purpose, they certainly inspire awe for the talent of the artists and artisans who made them. Do go see this show even – or especially – if you think tapestries are boring.

Galerie des Gobelins: 42, avenue des Gobelins, 75013 Paris. Métro: Gobelins. Tel.: 01 40 13 46 74. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Admission: €6. Through July 1. www.mobiliernational.fr

Reader Judith Schub writes that a short, very well-done film shown behind/under the main staircase explains the story of the “Chevalier de la Cygne.”

Support Paris Update by ordering books on Flemish tapestries from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.S., France, U.K.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite