Inventing the Past:

A Problematic Legacy

“Portrait Présumé de Charles Nègre sur la Tour Sud de Notre-Dame de Paris” (1853?), by Henri Le Secq. © Ministère de la Culture-Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Henri Le Secq

If, like me, you draw pictures of monuments and paint watercolors during holiday trips, a look at Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s drawings and sketches in the exhibition “Viollet-le-Duc: Les Visions d’un Architecte” at Paris’s Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine will leave you in awe of the skill of the renowned French architect.

Viollet-le-Duc, restorer of Notre Dame, Sainte Chapelle, Carcassonne and Pierrefonds, had an amazing technique as a draftsman. Surprisingly, we learn that he never went to school, but was educated privately by his uncle, the artist and journalist Etienne-Jean Delécluze, who believed in the value of travel and observation. The uncle organized journeys around France and Italy, allowing time for the young Viollet-le-Duc to draw Renaissance buildings, churches and antiquities as well as natural sites like Vesuvius and Etna.

The accuracy and minute detail of these drawing is impressive. Admittedly he made use of a “Camera Lucida,” a small instrument equipped with mirrors that can cast the image of an object onto a block of paper. One of these

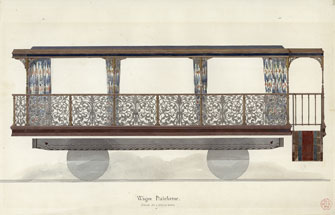

“Vue Extérieure d’un Wagon Plate-forme du Train Impérial” (1856), by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc © Ministère de la Culture-Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/image Médiathèque du Patrimoine

instruments is on display in the exhibition, and you can try it out. It is actually fiendishly difficult and requires constant minor adjustments of the squinting eye to trace your line along the image. When making a complex perspective drawing, you need to constantly modify your view of the real subject to make it fit onto the illustration.

Thanks to the process of constant observation, the young architect gained an intimate understanding of medieval construction.

Viollet-le-Duc’s major breakthrough came in 1840 when he was tasked with restoring the 11th-century Romanesque basilica at Vézelay. At the same time, he became involved in rebuilding the magnificent 13th-century Gothic Sainte Chapelle in Paris, an enterprise requiring stonemasons, glassmakers, carpenters, metalsmiths and other craftsmen. The young architect, fascinated by the smallest detail, oversaw the rediscovery of every aspect of medieval craft techniques and even brought in chemists to analyze the composition of medieval polychromatic paintwork to be applied in the interior.

He became so expert in the subject that he found the time to design an imaginary 12th-century cathedral, a model of which is on show. The virtuoso architect’s rigorous methodology led to his establishment of inflexible rules and principles of design and technique, which were published in his Dictionnaire Raisonnée de l’Architecture Française du XI au XVI Siècle. The dogmatic tone of this and other works have not been to everyone’s taste. Critics including Ruskin considered that Viollet-le-Duc was inventing methodologies that had never existed in the past: “A destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed,” the English scholar complained.

Every part of the decoration was the subject of his passionate involvement, including furniture, textiles and the designs carved in wood or stone. A deep understanding of geology and the organic structure of plant life, as well as a far-reaching knowledge of medieval legends and religious iconography formed the basis of his approach to the design of ornamentation.

The show includes sketches illustrating his ideas for grotesque gargoyles to adorn Notre Dame, combining imaginary beasts with caricatures of human facial characteristics. Viollet-le-Duc admitted this was pure invention, describing them as “quelques uns des animaux que Noé n’a pas jugé convenable d’introduire dans l’arche” (“some of the animals Noah decided not to bring aboard the ark”).

The fairy-tale Pierrefonds castle north of Paris

“Vue Cavalière du Château de Pierrefonds en Cours de Restauration” (1858), by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. © Ministère de la Culture-Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Image Médiathèque du Patrimoine

was a pet project intended for future occupation under the Second Empire by Napoleon III, but after the emperor fled France in 1870 it was never completed. Viollet-le-Duc had planned huge, spectacular interior murals, the impressive hand-painted cartoons for which are displayed in the exhibition.

Viollet-le-Duc’s voluminous writings on the principles of medieval architecture and the techniques used in ancient buildings remain a reference to this day, although his high-handed declarations and fondness for contrived or even fake conceptions of antiquity were rejected by many.

Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine: Palais Chaillot, 1 place du Trocadéro, 75016 Paris. Métro: Trocadéro. Open Wednesday-Monday, 11am-7pm (5pm on Dec. 24 and 31), until 9pm on Thursday. Closed Tuesday.Admission: €8. Through March 9, 2015. www.citechaillot.fr

Click here to read all of this week’s new articles on the Paris Update home page.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

© 2014 Paris Update

Favorite