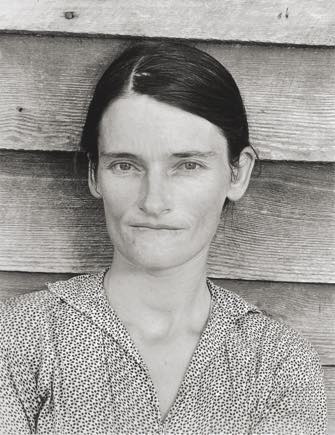

The Walker Evans (1903-75) retrospective that just opened at the Centre Pompidou came as something of a revelation to me. The American photographer’s Depression-era portraits of sharecroppers in Alabama are so famous that, at least for me, they eclipsed his other work, so it was a great surprise to see how fascinated he was with a great variety of other subjects.

Evans was a fascinating character in himself. A handsome young man from a well-off family, he arrived in Paris in 1926 at the age of 23 for his “year abroad,” hoping to become a writer.

He must have been a quick study, for he soon learned French well enough to translate Blaise Cendrars, André Gide and Charles Baudelaire (Near the end of his life, he told an interviewer that Flaubert had influenced his method and Baudelaire his spirit).

Typewritten versions of some of the charming essays he wrote in French for the Cours de Civilisation at the Sorbonne, that eternal refuge of expats in Paris, are on display, along with some of the photos he took, which already show his talent and originality, although at the time he did not consider himself a photographer.

Back in America, he turned to photography as a career and ran with the arty crowd in New York, embracing the New Vision style of photography, with its odd angles and graphic effects.

His work was soon being published in revues, but he moved away from this modernist style under the influence of writer Lincoln Kirstein and photographer Berenice Abbott, turning toward what was to become his lifelong obsession with documenting and cataloging American popular culture and ordinary people.

Evans’s true moment in the sun was the result of those Depression-era photos. Employed by a New Deal program, the Farm Security Administration, he traveled the backroads of America, photographing small-town life. During a break, he joined a friend, the writer

James Agee, in Alabama, where they lived with poor sharecroppers for three weeks, studying their lives for an article that was never published but that became in 1941 the seminal book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

The Metropolitan Museum in New York, which owns most of Evans’s work, sums him up beautifully: “His principal subject was the vernacular—the indigenous expressions of a people found in roadside stands, cheap cafés, advertisements, simple bedrooms, and small-town main streets. For fifty years, from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, Evans recorded the American scene with the nuance of a poet and the precision of a surgeon, creating an encyclopedic visual catalogue of modern America in the making.”

Among the hundreds of photos in this exhaustive exhibition, besides the images of sharecroppers, there are many gems. Some of my favorites are “Truck and Sign” (1928-30), showing men loading an enormous sign reading “Damaged” onto a rather small truck; “Main Street, Saratoga Springs, New York” (1931), a view of the rain-slicked street from

on high with nary a human in sight, just a row of tall, leafless trees standing gracefully alongside a lineup of squat black automobiles parked aslant; and the humorous “Resort Photographer at Work” (1941), showing a lady photographer, very chic in her sunglasses and

heels, squatting down to look through her camera at her subject: an older woman, all dolled up and wearing a picture hat, sitting stiffly on a low wall in front of a fake beach scene complete with palm trees, pelicans and a crocodile.

You may be surprised to see that Evans pioneered many photographic approaches that we now think of as avant-garde and that influenced many photographers who came after him. When I saw the way he catalogued types of buildings, I couldn’t help but think of the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, for instance, while his stark, straight-on, warts-and-all portraits certainly influenced such photographers as Diane Arbus and his street photography others, among them Robert Frank.

Interspersed in the exhibition are several of his

charmingly naive and colorful paintings.

This is a rare opportunity to see the full range of Evans’s work, the first time such a retrospective of his work has been held in Europe. Don’t miss it.

Favorite