There are a fair number of reasons that you might be drawn to the Marais for the current exhibition at Le Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme. You’re the kind of person, say, who revels in puzzles, brainteasers, artifacts and aphorisms, or whose idea of a fun day out involves passionately poring through footnotes and catalogs at the National Library. Maybe you have a fetish for calligraphy, curios and cross-references. Or you’re simply the kind of person whose mind and heart palpitate over Jewish mysticism, German idealism and aesthetic theory. The most compelling reason would be that you are a Walter Benjamin fanatic. To his aficionados, he’s endlessly fascinating. But then some of you may be thinking right now, uh, Walter who?

Walter Benjamin was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin in 1892, the oldest of three children. His father owned an antique shop, which might explain his penchant for collecting, or “rag picking,” as he called it – everything from peasant handiwork to picture postcards, poetry, texts, commentaries, manuscripts, scraps, citations, images, lists, diagrams, artifacts and systems – resulting in an impressive legacy, much of which is on display in the exhibition.

The mysterious circumstances of Benjamin’s death in 1940 at the age of 48 have spawned conflicting theories. On the medical certificate, the cause of death is cerebral hemorrhage, but some have suggested suicide, others an accidental overdose, still others assassination by the Nazis. We may never know the truth, but what we do know is that, after seven years of exile in various parts of Europe, and having jumped homes at least 28 times, Benjamin’s final journey led him from Paris to Lourdes to Marseilles, via the Pyrenees, and eventually to Portbou, Spain, for a one-night stay in room No. 4 on the second floor of the Hotel de Francia, to be exact. The morning after – September 27, 1940 – he’d planned to set sail for America and join his friends Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno to work at the Frankfurt School in New York. Instead he was found dead in his hotel bed, leaving behind a leather suitcase, a gold watch, a pipe, a passport issued in Marseilles by the American Foreign Service, six passport photos, an X-ray, a pair of spectacles, magazines, letters, papers and some loose pesetas.

In his brief but prodigious lifetime, Benjamin was not only a keen, judicious collector (or “true resident of the interior,” in his words) but also the quintessential Man of Letters: a literary critic, philosopher, sociologist, translator and essayist. He was particularly fascinated by the works of Goethe, Kafka, Kraus, Proust and Baudelaire. In 1936, he published his most influential essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. But it was his unfinished work-in-progress, The Arcades Project, that would certainly have become his masterpiece: an extensive, encyclopedic “literary montage” about the 19th-century flâneur, for whom idling, perambulating, window-shopping and observing was a poetic art form set by the pace of turtles (an all-the-rage pet in those days) through the “passages” or arcades of Paris. For Benjamin, these arcades, with their fragmentary arrangement of all-and-sundry goods, held the key to historical understanding while seeming to exist outside place and time.

While it may sound chock-a-block with things, the exhibition is actually quite tiny – most of it displayed in 13 sections in little glass cases filled with detailed documents that require rather concentrated peering, eye-focusing and re-focusing – some anti-glare specs would help. And when I say tiny, I mean it: throughout his life, Benjamin obsessively scratched out these minuscule scripts in German and French.

His penchant for list-making gives me an excuse to offer you a list of the sections: Scrappy Paperwork (collecting and dispersal), From Small to Smallest Details (micrographies), Physiognomy of the Thingworld (Russian peasant handicraft acquired in Moscow), Daintiest Quarters (notebooks), Travel Scenes (postcards from Tuscany and the Balearics), Sibyls (mosaics in Siena), Constellations (graphic forms that demonstrate thought processes), A Bow Being Bent (diagrams structuring his research material), and Hard Nuts to Crack (distortions, shifts of meaning, riddles, brainteasers, word games).

Extremely touching are the “Opinions et Pensées,” which track the intellectual development – and turns of phrase – of his son Stefan. In February 1926, for example, Stefan asks what a “pampire” (meaning “vampire”) is, then says, “my stomach is grinning” (to indicate that he’s really looking forward to something). Benjamin loved non sequiturs of this kind – of any kind, in fact.

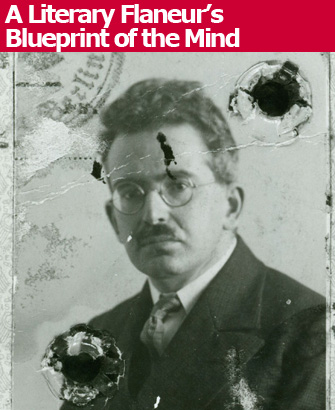

These collectibles communicate among themselves and together give rise to his “world of secret affinities.” But other items in the show loom larger: on the borders of these micro-exhibits are blown-up, framed photos of Benjamin from childhood to middle age; of his family, friends and colleagues; and of arcades, shop fronts, street signs, alleyways, and public and private bourgeois lives.

One of my favorites is an intimate snapshot of him taken by Gisèle Freund: bespectacled and mustachioed, wearing a three-piece wool suit and tie, fountain pen in hand, hunched over his books in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Also on display are his private and work-related correspondences with Adorno, Bertolt Brecht, Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt, to name but a few. In 1927, he wrote to Alfred Cohn: “I carry the blue book [his notebook] with me everywhere and speak of nothing else… I am sure that there is nothing else of this kind as pretty in the whole of Paris, despite the fact that, for all its timelessness and unlocatedness, it is also quite modern and Parisian.”

Unlocated timelessness, indeed; whether or not you can make sense of it, there’s a sublime beauty in this collection – it’s a personal portrait of a fascinating scholar, the great architect drafting a schematic blueprint of his mind. But if you are at a loss, Walter Benjamin’s Archive is available in print form and now in English translation; it’s a spectacularly impressive, unique sort of catalog that fills in all the fascinating details.

Benjamin, like Thoreau, believed that each walk should be approached as an end in itself, not as a journey from which to return. This show is perhaps not the same kind of intense yet spontaneous stroll for everyone, but I never wanted it to end, and it seemed all too brief. Benjamin loved repetition on the grounds that “Once is as good as never”; in this case, I’ll have to disagree, although I wouldn’t mind going back for more.

© 2011 Paris Update

Favorite